| NYSE Paper Ticker Tape: November 15, 1867– March 31, 1994 |

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

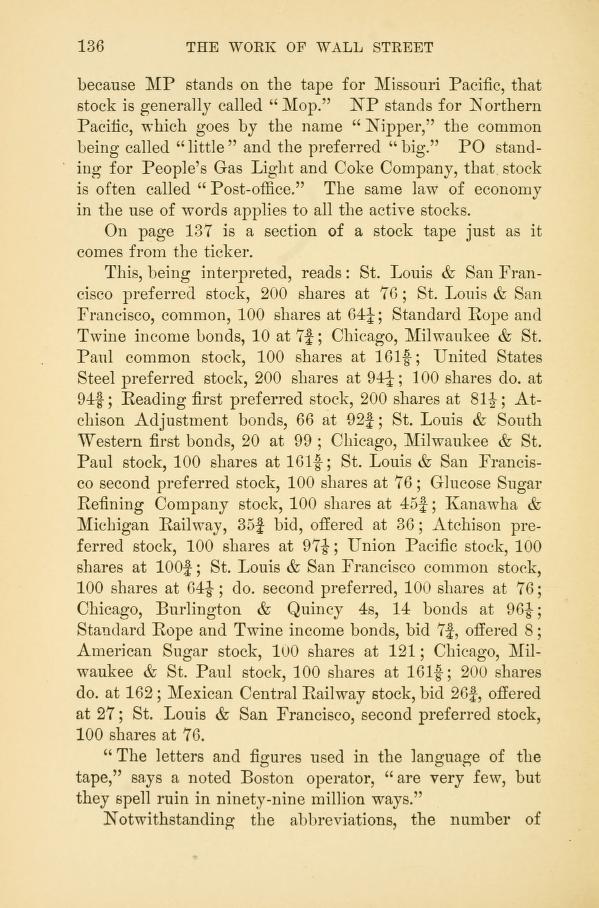

| Dating Ticker Tape: Introduction |

One of my students asked me how many stocks I needed to use to do this, and I found that if I took

just the first two stocks, I got the same answer. Stock prices are so volatile that there was only one

day that the wildly moving price numbers on my first two stocks fell within the ranges in the databases.

It just so happened that the first two stocks I looked at

were wild enough that they determined uniquely the day, but that was not true for any pair of stocks.

I found that I could pinpoint the day using any four of my 10 stocks. So, 10 stocks were sufficient, but, in general,

only four were necessary.

| Dated Examples of Ticker Tape |

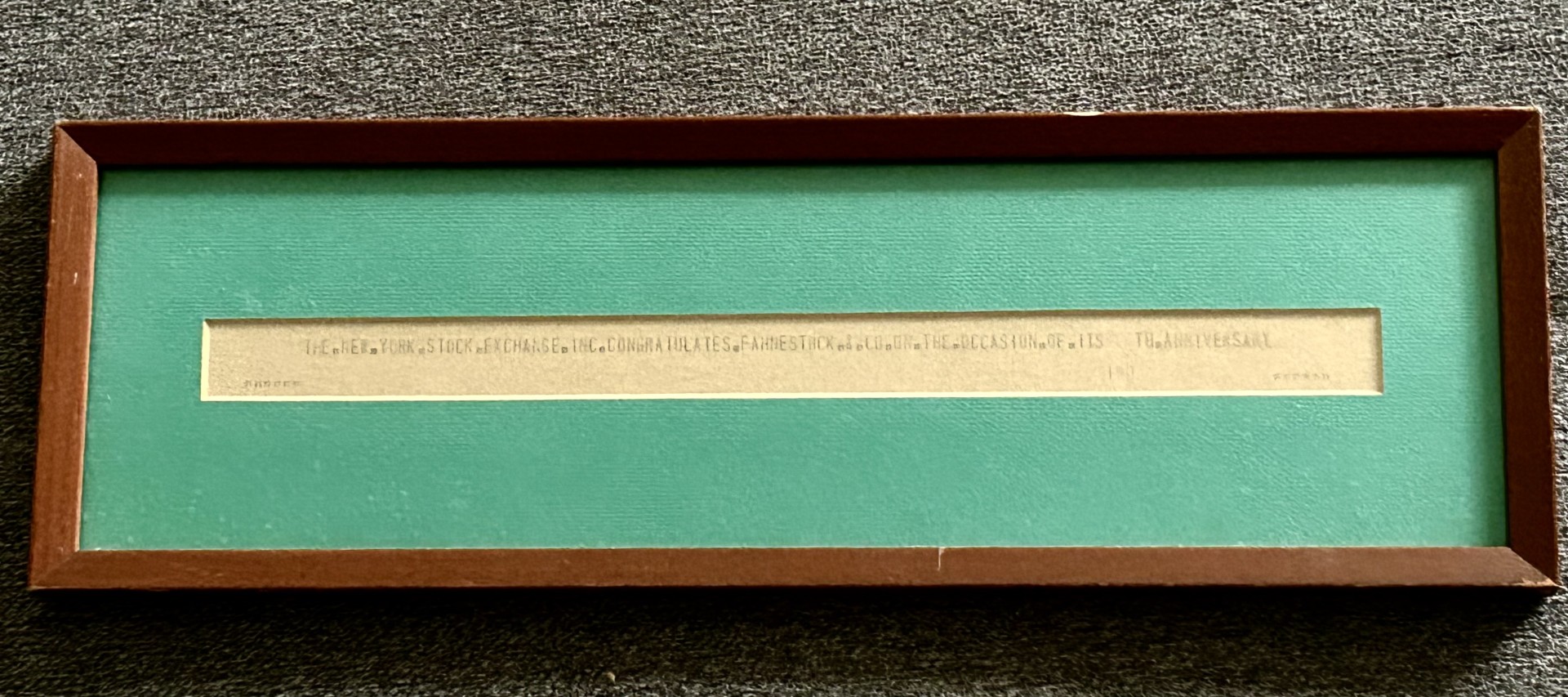

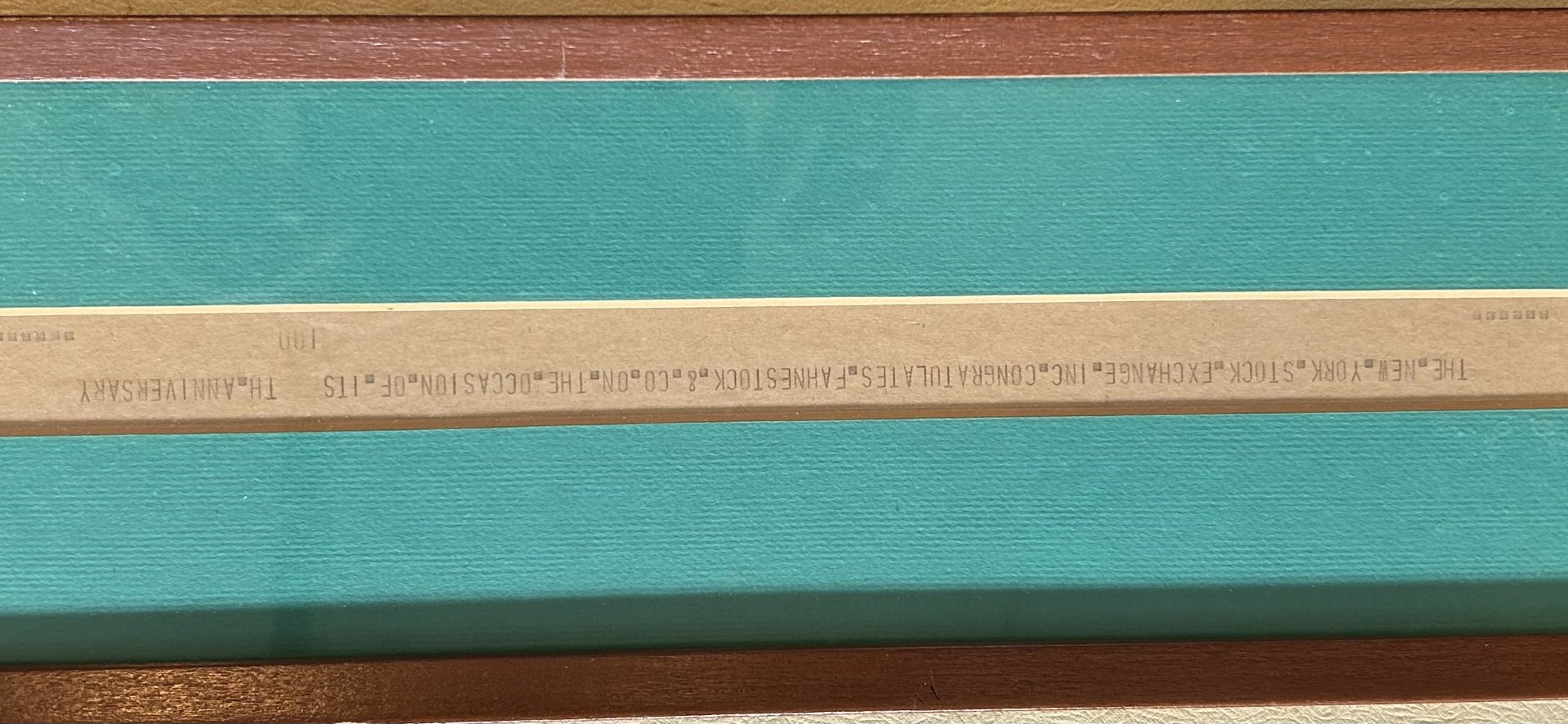

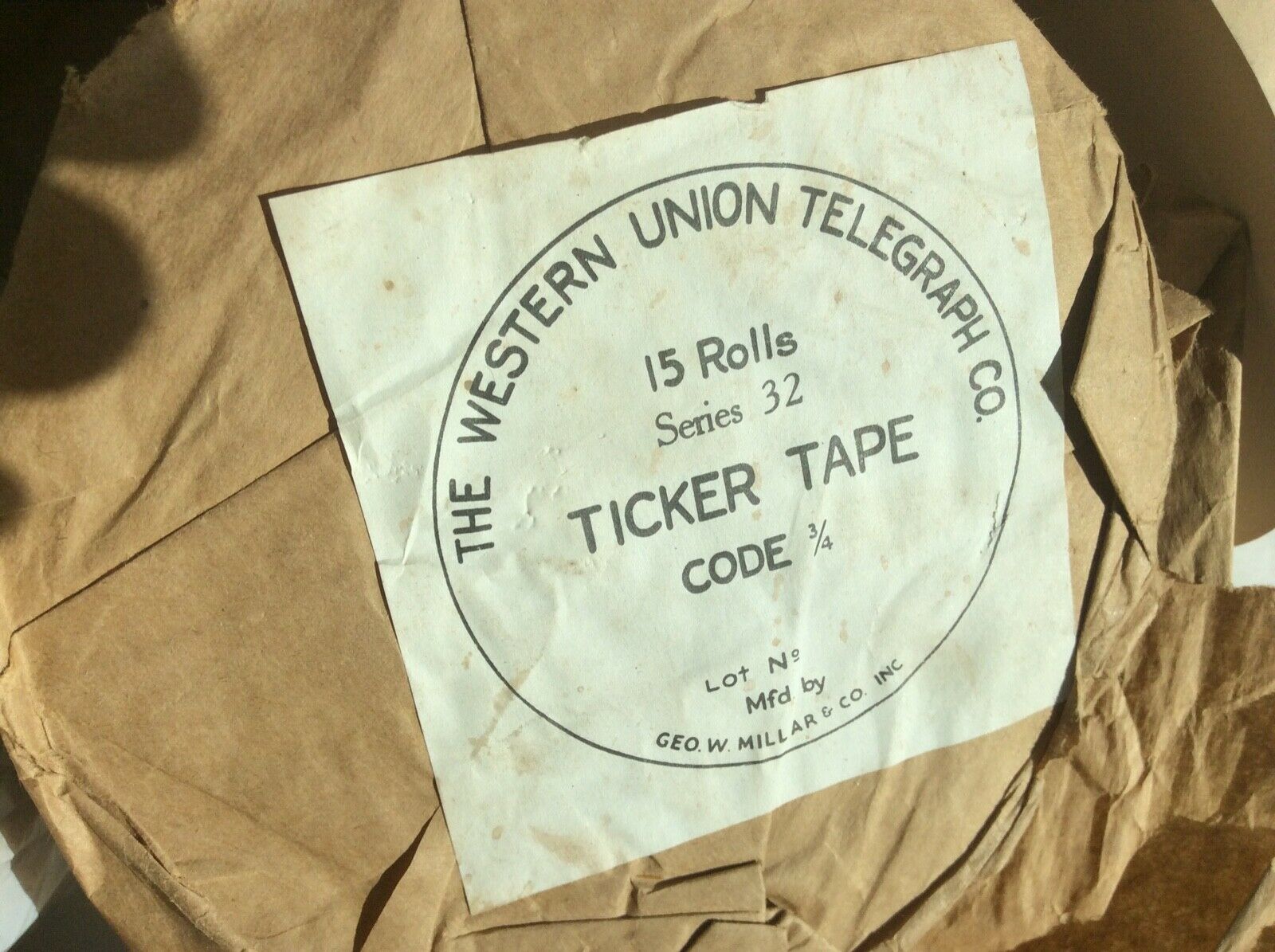

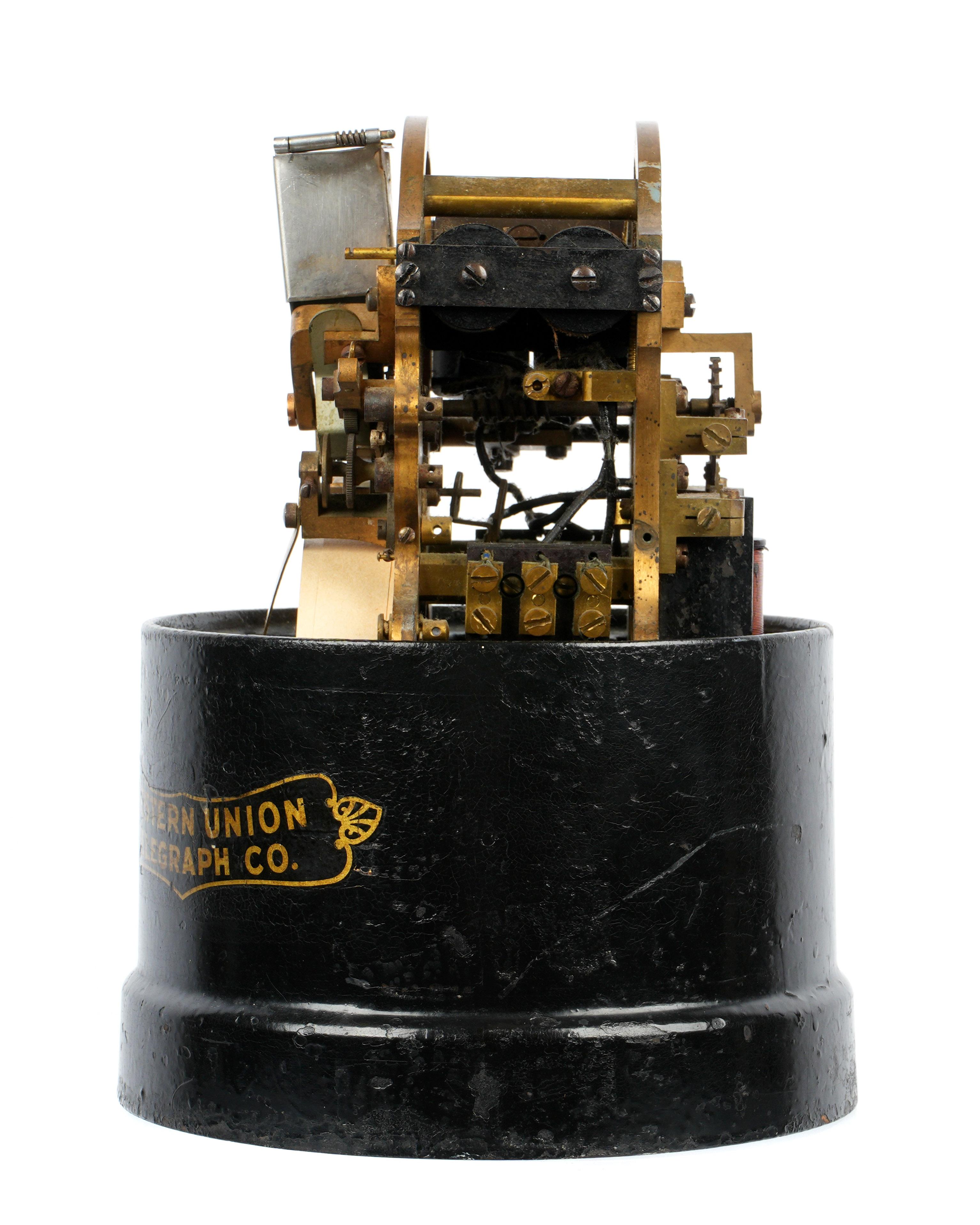

There are no stock prices, but note the fading dots because the type wheel is not re-inked. Note also that the type is relatively clear and clean and the characters are not preceded by a dot on either line. I think this is 3/4-inch tape printed on a Western Union Black Box 5A. I think it was printed especially for young Master Jack Watts when he visited the NYSE in the summer of 1939. To put this in historical context, this day was just 2 1/2 months before Britain declared war on Germany, to start WWII. Here is a photo and obituary of a "Jack Watts" from Jefferson Iowa. If this is the same person, then he was 11 years old in mid-1939, which fits with the story.

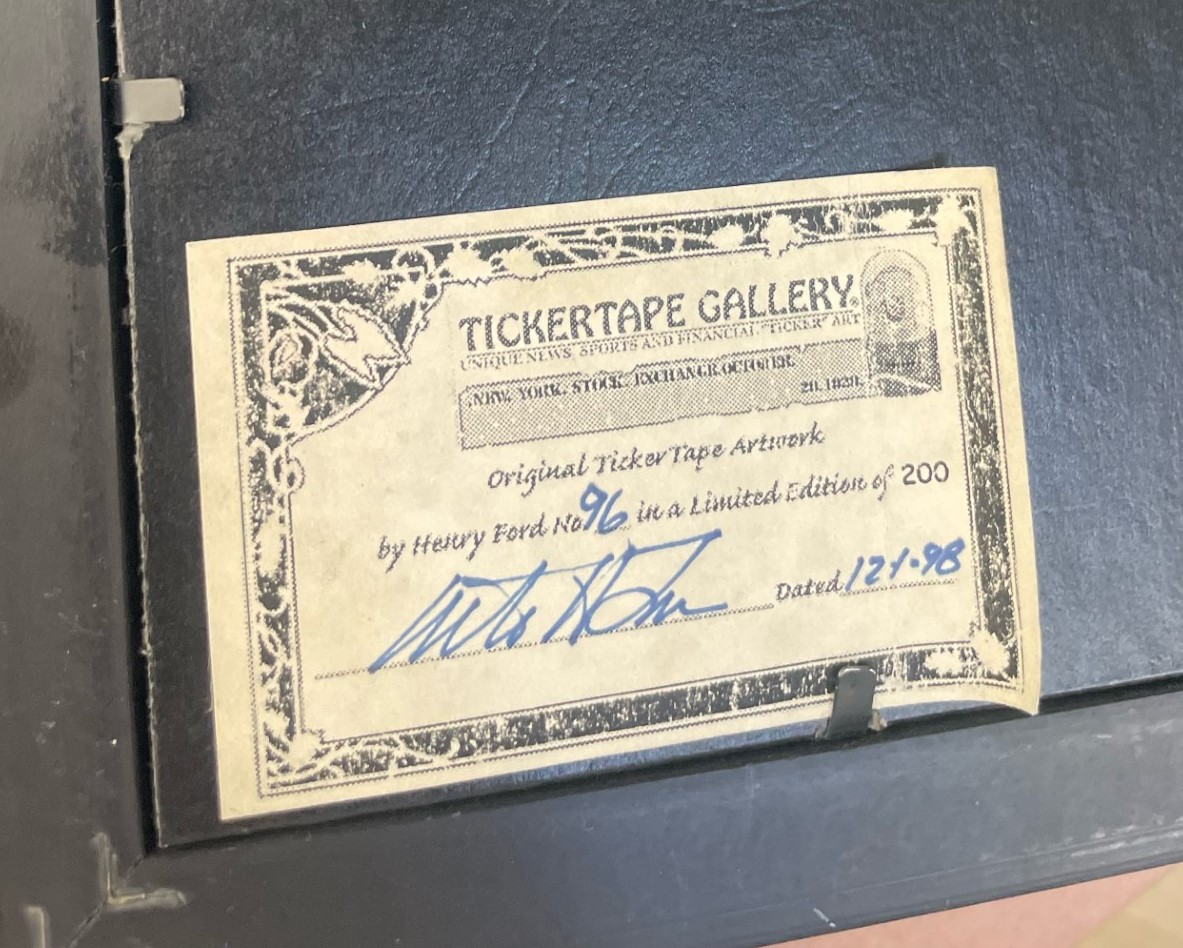

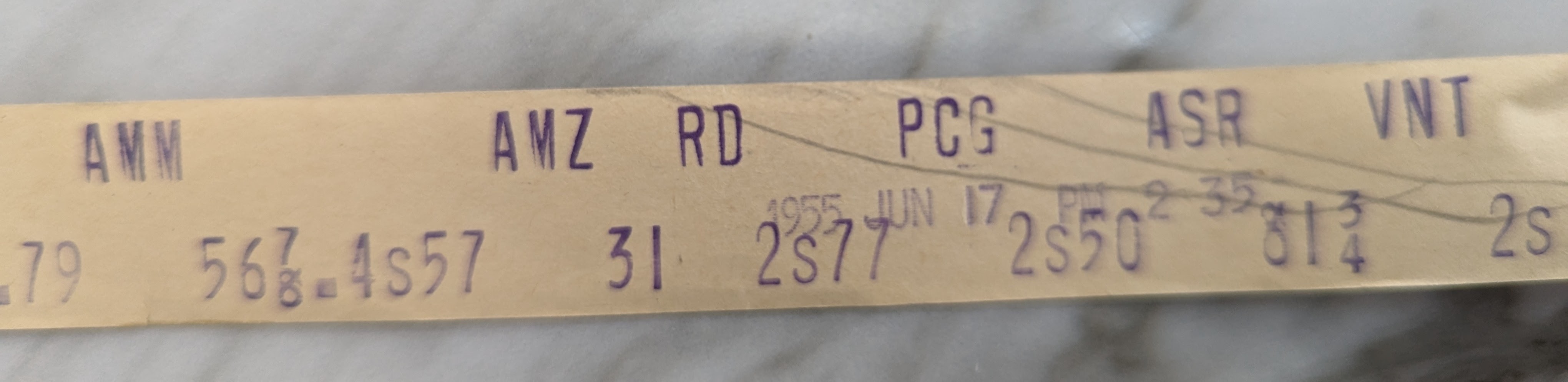

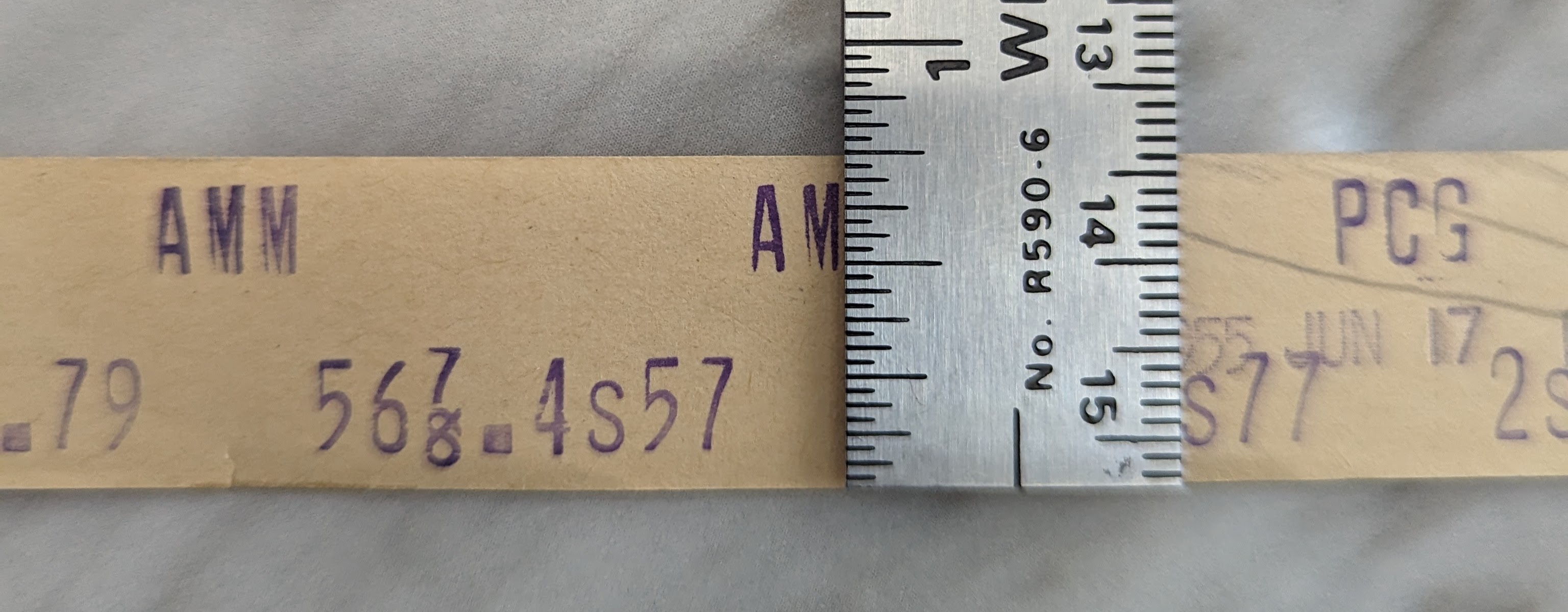

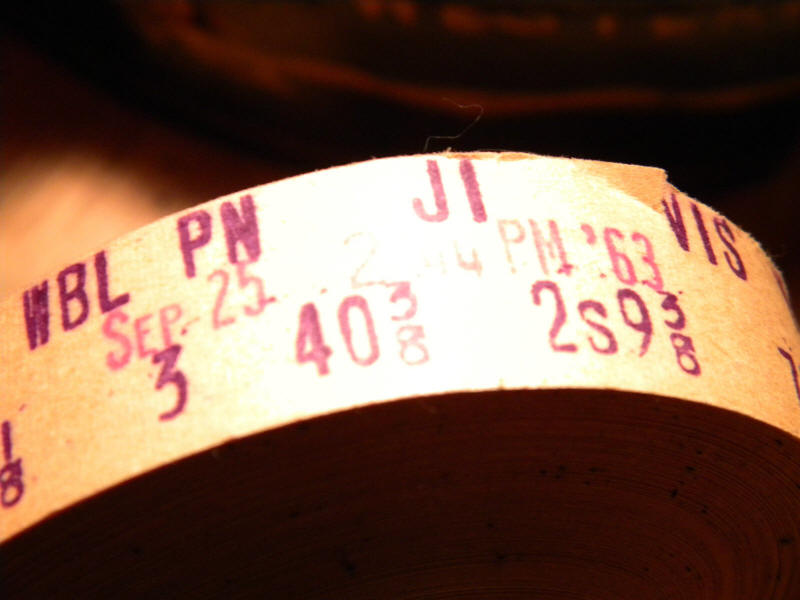

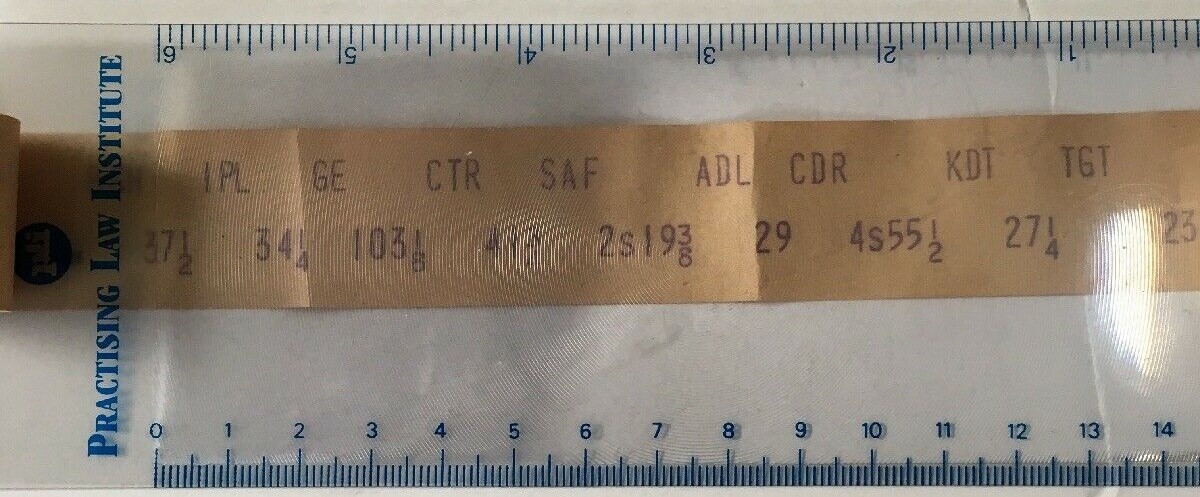

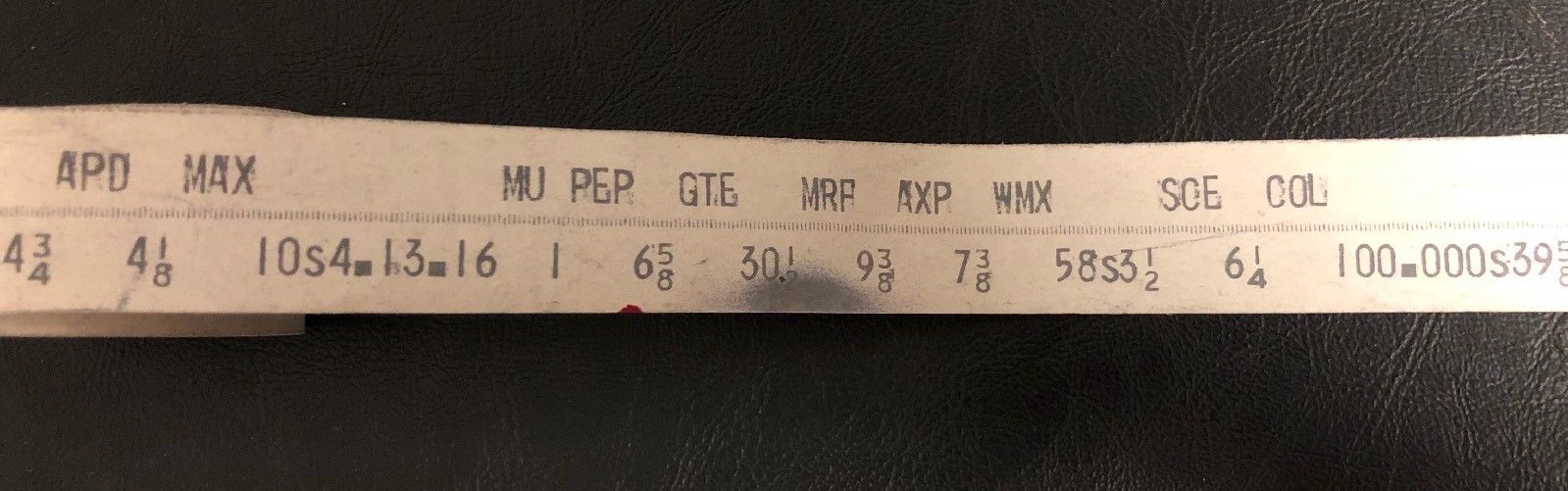

I was surprised initially to find that the stamped date is accurate. (I think my skepticism arose because half of all ticker tape I have seen since about 2015 has been fake or fabricated after the fact, often with false dates attached. This tape, however, is 100% genuine.) I pulled nine of the symbols and prices from the tape and compared them with daily high prices and low prices on stocks between 1926 and 2019 and there is only one day when all nine price stamps fall between the recorded highs and lows: Friday June 17, 1955. So, the date stamps are correct.

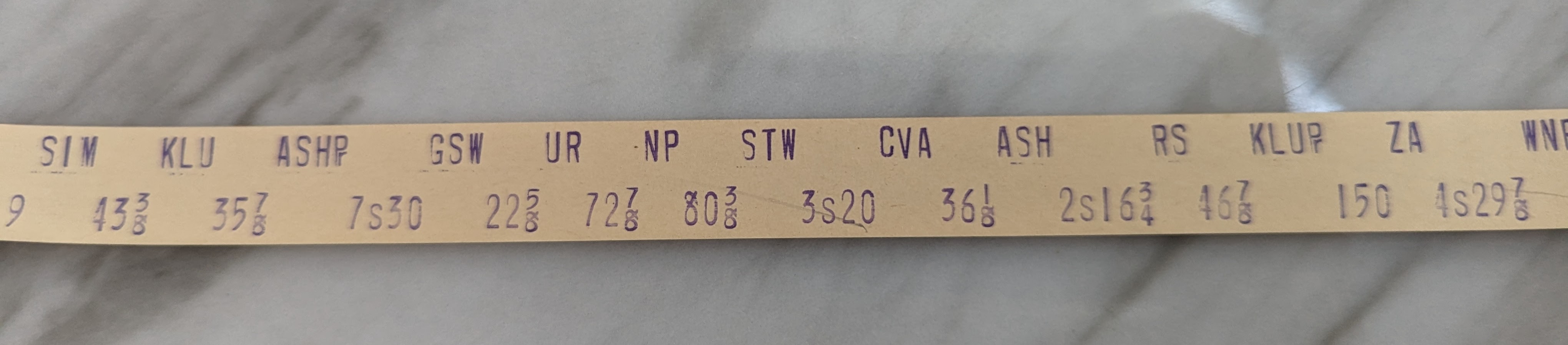

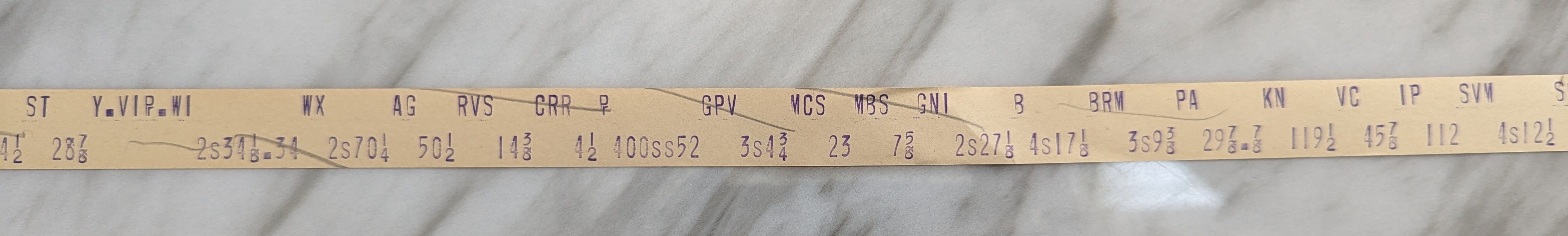

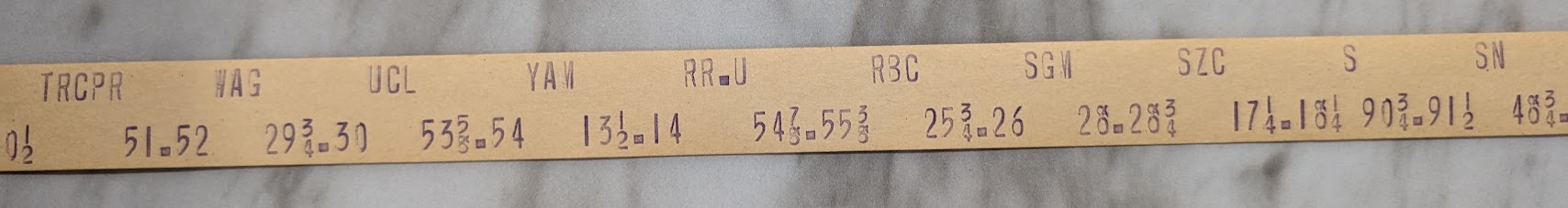

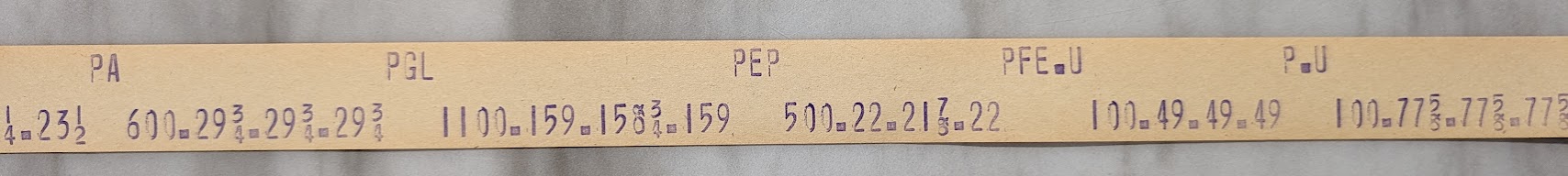

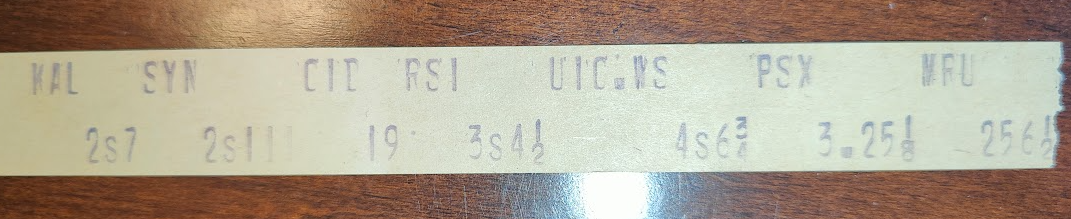

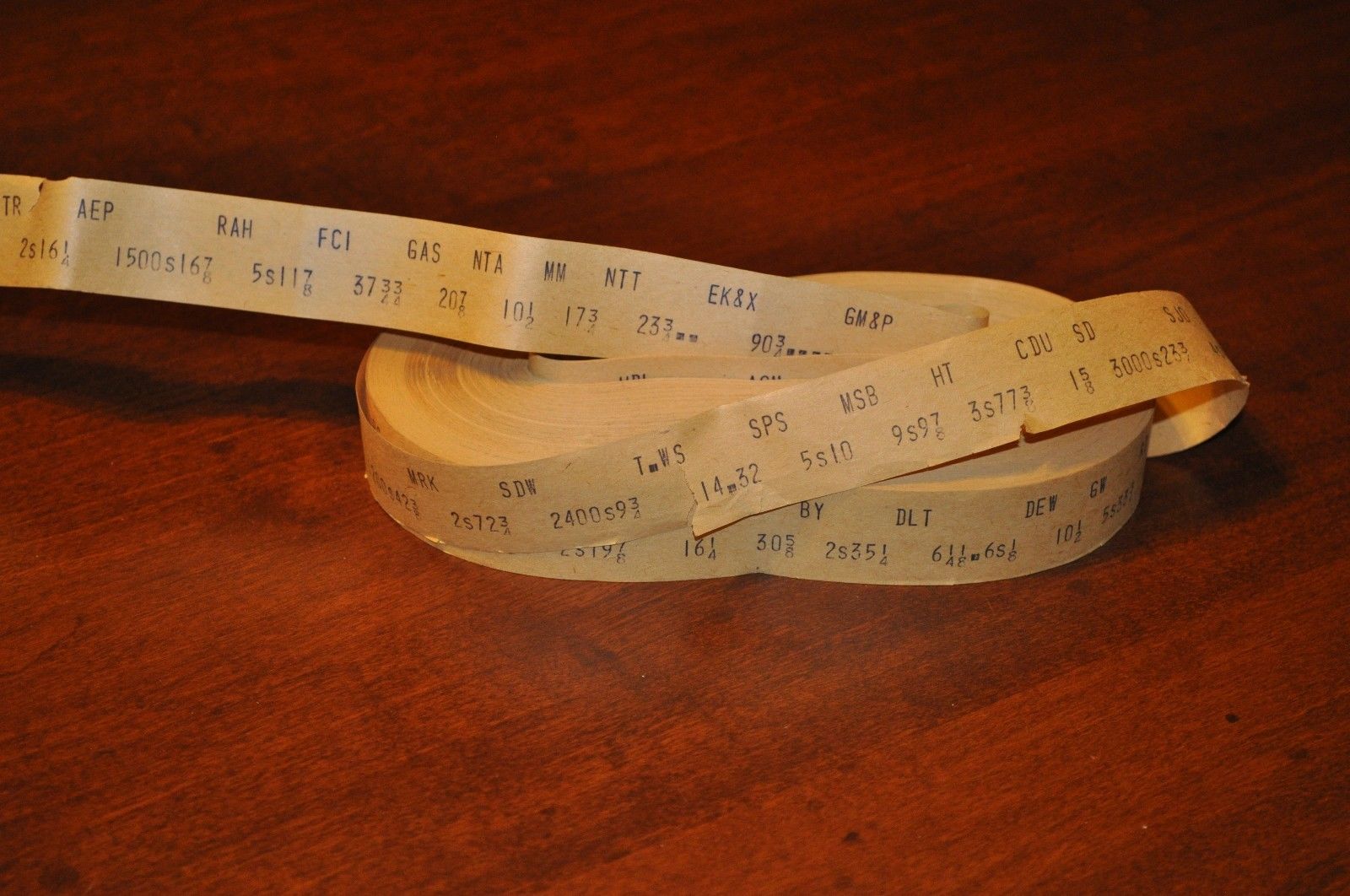

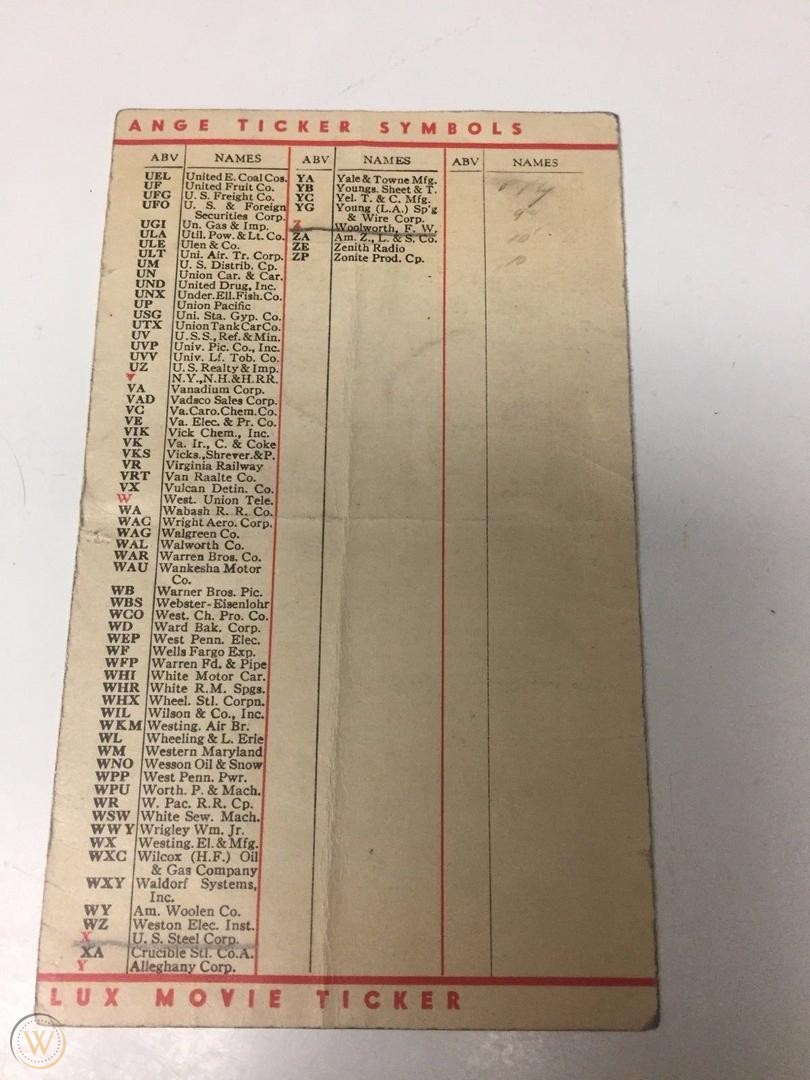

This tape is a clear microcosm of American business in the 1950s. It is full of metals, oils, electrics, sugar, paper, and railroad stocks, many of which still exist today in some form. There are some famous names there among the ticker symbols I can see: PCG is Pacific Gas and Electric; WX is Westinghouse Electric; KN is Kennecott Copper; RD is Royal Dutch Petroleum (now aligned with Shell); KLU is Kaiser Aluminum; ZA is American Zinc; GSW is Great Western Sugar; ASR is American Sugar Refining; CRR is Carrier (the HVAC people); IP is International Paper; PA is The Pennsylvania Railroad; NP is the Northern Pacific Railroad; and STW is Stanley-Warner (which was movie theatres acquired by Warner Bros.).

The tape is unusual for another reason: The last time stamp says 2:35PM, but in 1955 the NYSE was open until 3:30PM.

Nevertheless, all but one price I looked up was a closing price. That is, a last price for that day.

So, I have to figure that not much was going on in terms of trade during that last hour on Friday

(or the time stamp is wrong, possibly out my one hour). I looked up the Wall Street Journal from the Monday following, and it said

that the Friday was an average sort of day. I already knew that, however, just from reading the tape because

on busy days the ticker did not print the full prices, just the last digit and the fraction, to save time,

yet here we have full prices reported. So, I think it was a leisurely Friday afternoon in the summer.

The same woman surprised me months later by saying she found a second roll of tape, which I confirmed to also be from Friday June 17, 1955. I could tell from the images that it is not from the same ticker machine as the first roll. Every stamp below is from after the close of trade. I suspect that the second roll contains the last hour of trade from June 17, 1955. So, the two tapes combined likely cover 12:13PM to 3:30PM on Friday June 17, 1955.

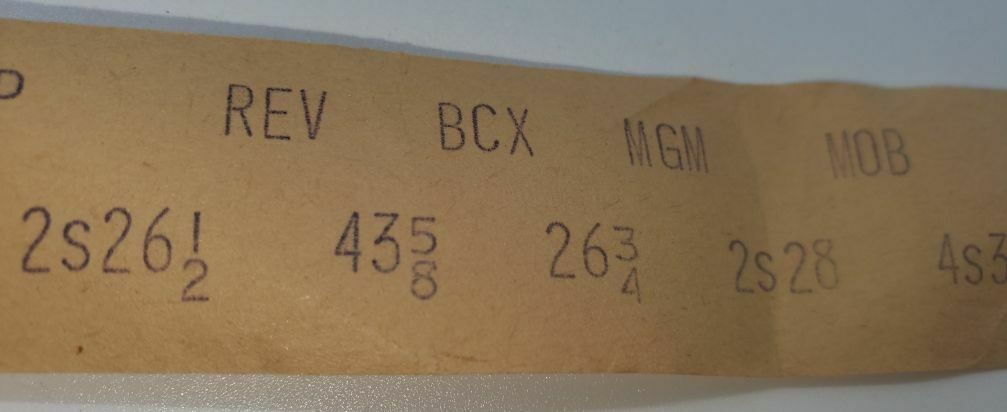

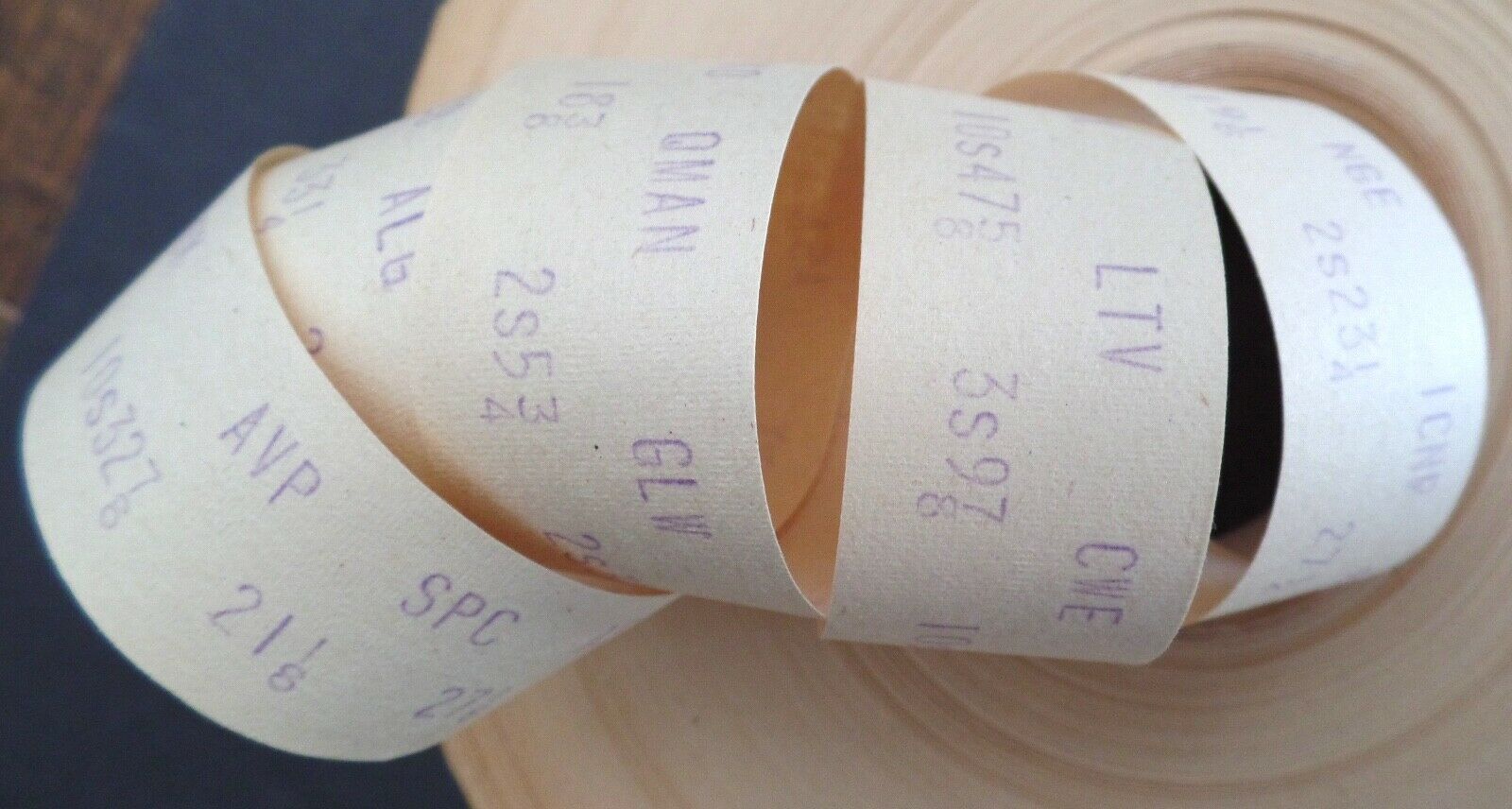

Here are some closing bid and ask prices on Friday June 17, 1955 (see the note on "runoff" further down the page).

The bid price is the price that the NYSE market maker bids for your stock and the ask price (or "offer" price) is

the price that the NYSE market maker offers stock to you at. The difference between the ask and the bid is the bid-ask spread.

These spreads are very wide. That may just be because they are closing quotes, and not firm prices for trade.

In 1955, the NYSE market maker was called a

specialist. Nowadays, the NYSE market maker is called a designated market maker (DMM).

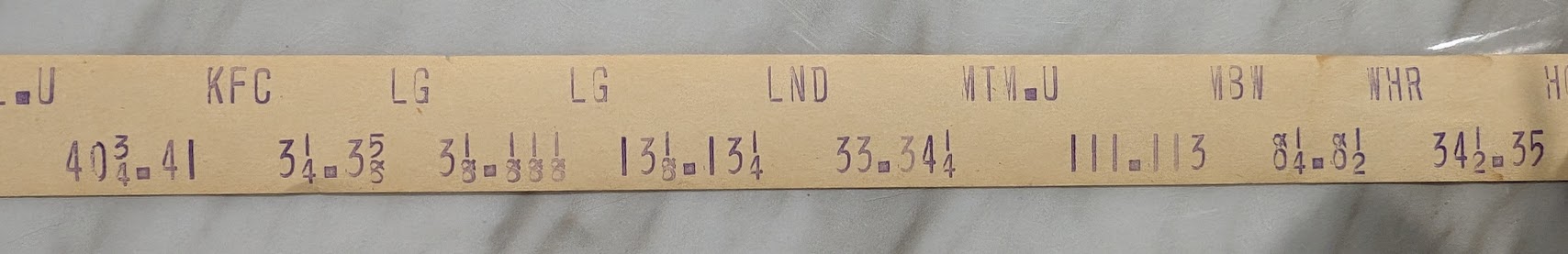

Note KFC on the third image down. This is 11 years before the fast food company listed its stock on the exchange. KFC here is Kropp Forge Co.

Although the fast food company existed in '55, it was only three years old, and I suspect that the

initials KFC meant nothing to anybody yet, beyond Kropp Forge Co.

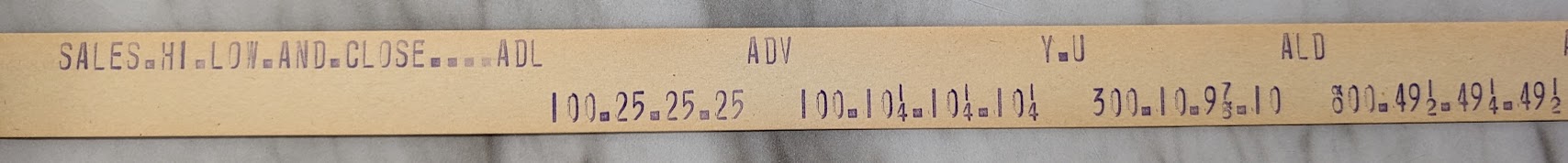

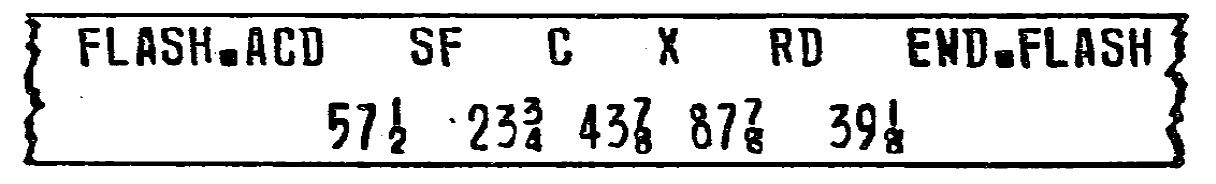

Here are sales, high, low, and close prices (see the note on "runoff" further down the page). I think the sales are actual counts of shares.

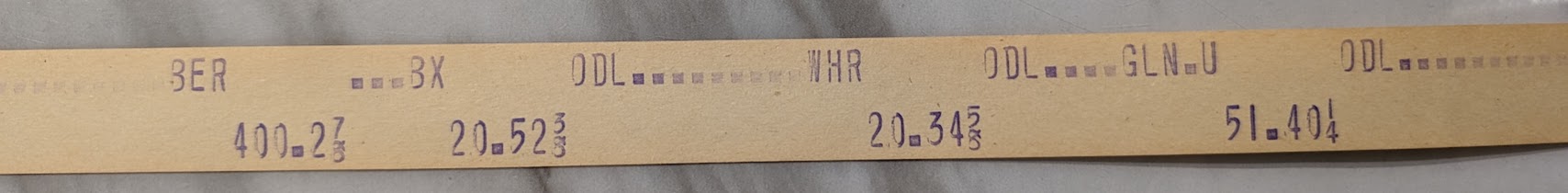

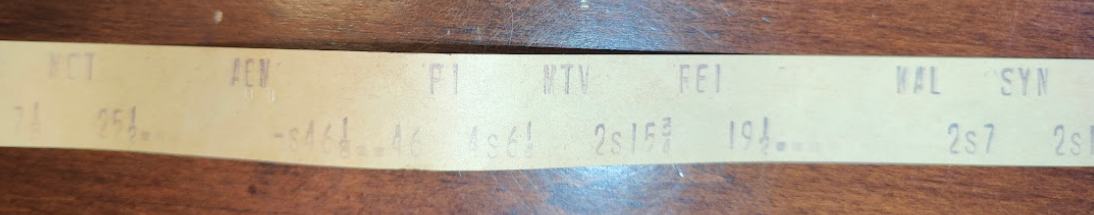

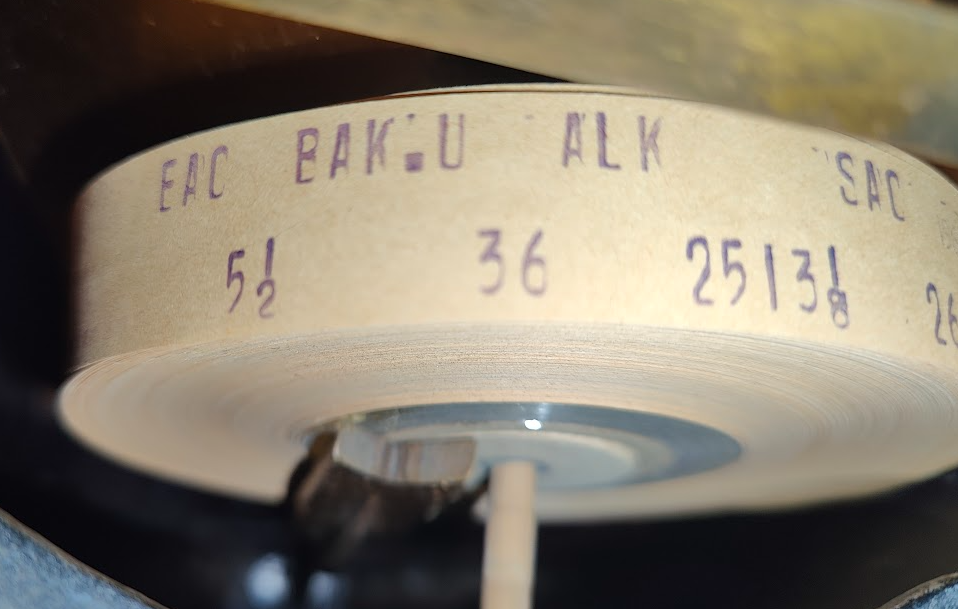

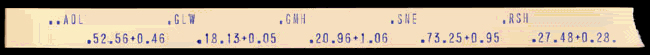

Note Y.U and PFE.U here, and GLN.U in the odd lots below. I am not sure what the .U suffix means,

but I did notice that in one case (BAK.U on April 26, 1966, lower down the page) the stock jumped dramatically

the next day. Could it be some sort of unissued stock that trades the next day, like "when issued" stock?

Here are odd lot sales. That is, sales of fewer than 100 shares.

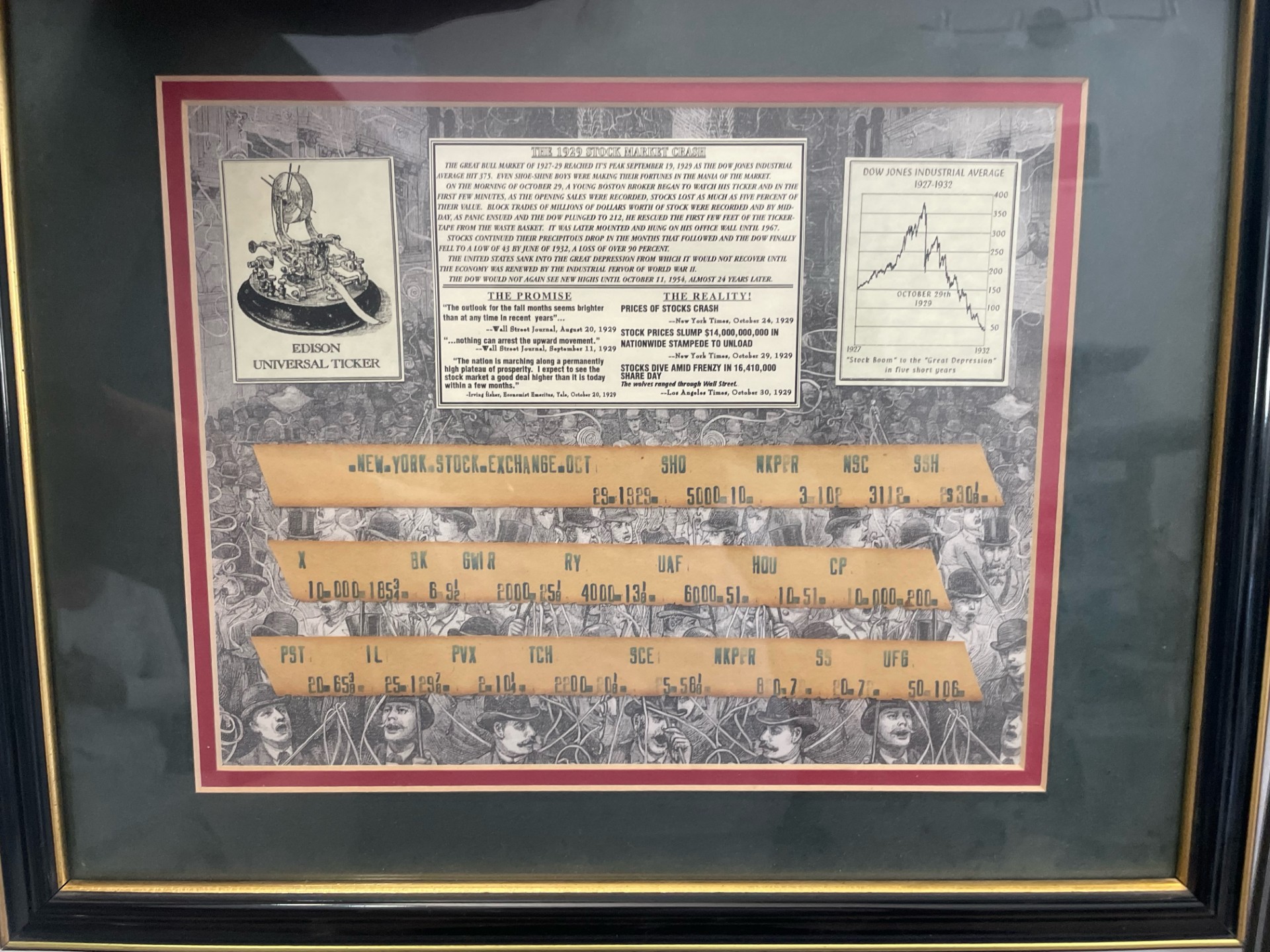

His ticker machines are rare older models, from before the great depression. So, I was curious to see whether his ticker tape might

possibly be pre-1929. That would have been a very unlikely outcome—because I have never seen any pre-1929 ticker tape.

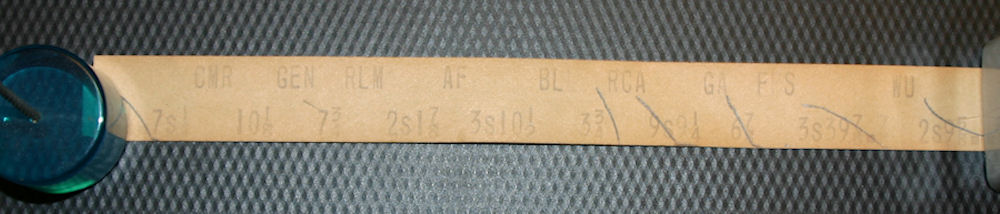

He sent me an image, below, and I dated his tape to Thursday March 9, 1961. It can be no other day.

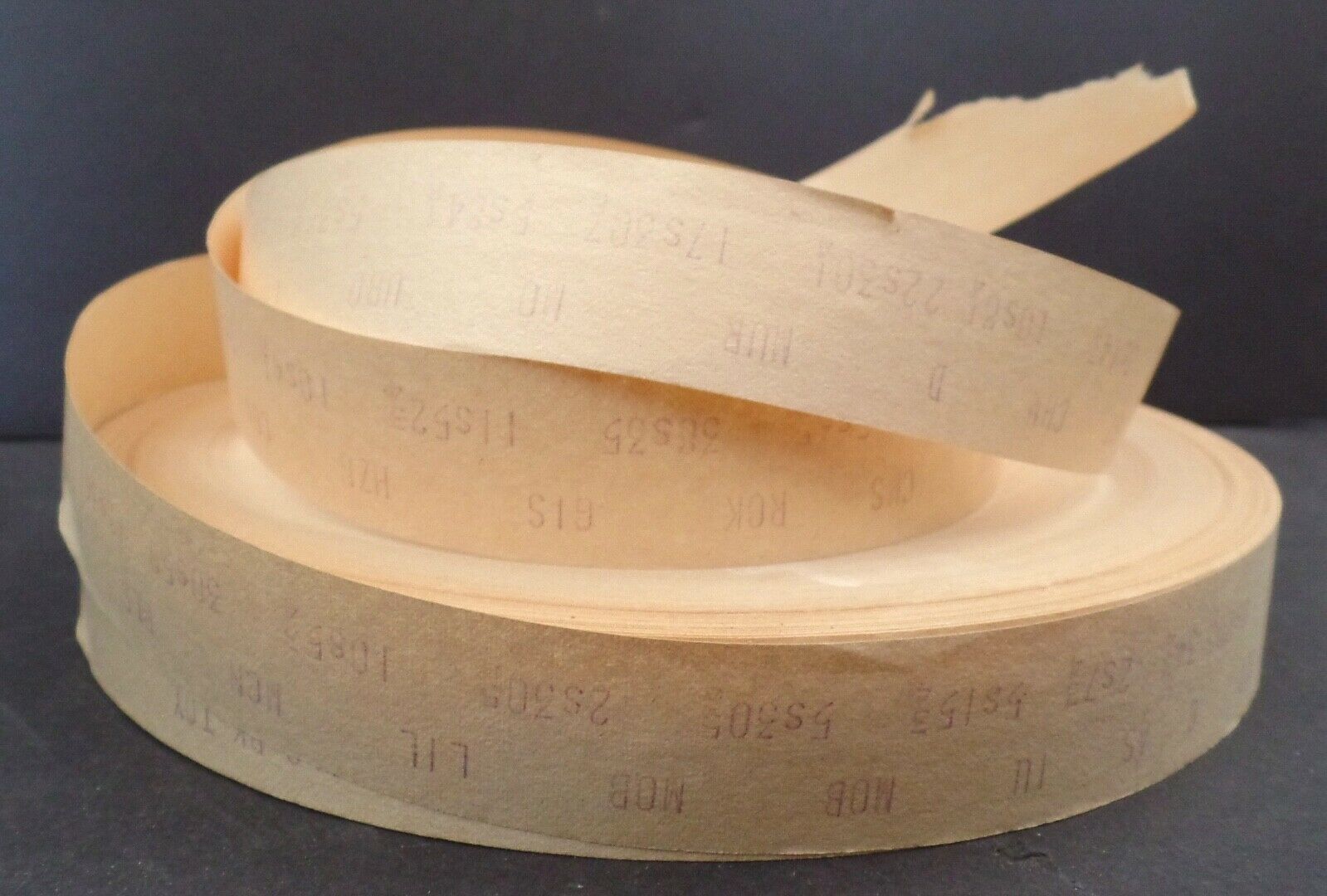

The symbols on the tape, their price stamps, and their recorded stock price ranges on Thursday March 9, 1961 are:

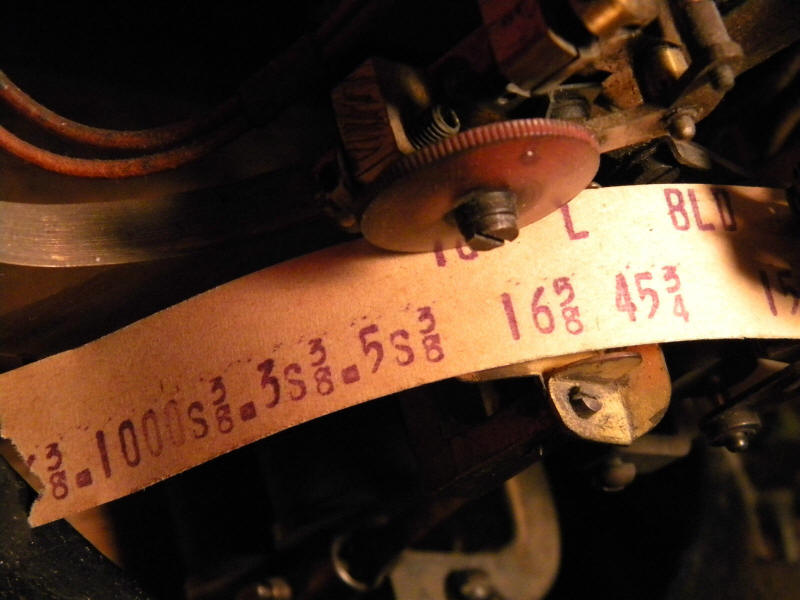

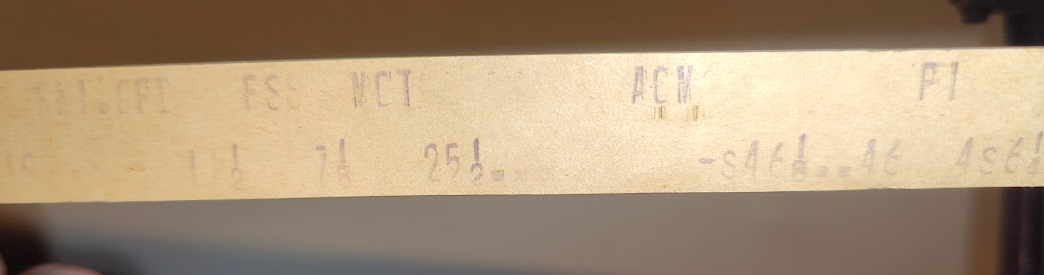

I noticed that six of the nine stocks have the handle (i.e., the leading price digit(s)) dropped from the stock. For example, Radio Corp of America (RCA) was at 59 1/4 but the print shows only 9 1/4, and Western Union (WU) was at 49 5/8 but the print shows only 9 5/8. When the market was busy, dropping leading digits helped to reduce delays in the tape. (It was assumed that the traders were familiar enough with the market that they did not always need the handle; dropping the handle, and dating ticker tape with dropped handles, are discussed further in the August 26, 1966 example, further down this page).

As soon as I saw the image of the tape, I knew the handles were missing on some of the stocks, and that it must have been a busy trading day. So, after dating the tape, I went looking for newspaper headlines from the next day, expecting to find reports of heavy volume. The New York Times (NYT) headline on the Friday morning (March 10, 1961) says, of Thursday March 9, "Market is mixed as volume soars: Trading exceeds 6 million shares for the third time since 1933." So, it was one of the three busiest trading days in almost 30 years. This unusual activity may be why the broker (or whoever) kept the tape at that time.

For recent comparison, note that between January 2, 2019 and November 18, 2022, daily NYSE trading volume varied between 1.0 billion and 11.6 billion shares, with an average of 4.0 billion shares per day (NYSE, 2022)—an average that is over 650 times the trading volume on March 9, 1961. The median trading volume over this sample period was marginally higher than the mean, at 4.2 billion shares. The mean during the more recent Jan–Nov 2022 period was higher still, at 5.0 billion shares. It looks like the largest-volume trading day in 2019–2022 was January 27, 2021 (11.6 billion shares), when the Fed's FOMC meeting policy decision mentioned deteriorating trends in economic activity. (Aside: On this day there was also a doubling in price of GameStop stock, from 36.99 to 86.88, with 373.6 million shares traded. It had also doubled the previous day on 714.4 million shares volume.)

I figure they must have given flash prices for leading issues only, cutting into the ticker feed to report them on time, rather than with a delay. (The notoriously unreliable Investopedia says that "Flash prices came into existence with the advent of computerized stock trading during the mid-1990s." My NYT article is from 1961, however, and it is not described as a new development.) Second, Hammer shows a simulated alternative ticker tape that was 3–3 1/2 inches wide, instead of the 3/4 inch tape in use at the time. He says that this wider tape was from a prototype of a new faster ticker machine that printed quotes horizontally across a vertically-printing tape, one quote per row, and was much faster than the existing ticker machines. The NYSE said that it would take two years of development before the newer faster ticker machine replaced the older one. As far as I know, however, the prototype never came to fruition. There might have been some push-back from brokers and traders used to reading horizontally-printed ticker tape. In fact, we still have horizontal ticker tape, albeit in electronic form, 60+ years later. So, there must be something about the horizontal format that appeals to the human eye; maybe it is that your eye does not have to jump down to the next row at any time.

<\center>

<\center>

Missing handle(s) makes the matching process a bit more complicated, because my Excel code has to allow for multiple

possible unknown handles. My Excel code looks for the full price on that day in the database, or the full price with the

first digit shaved off, or the full price with two digits shaved off (I also had to do this with the ash tray example below).

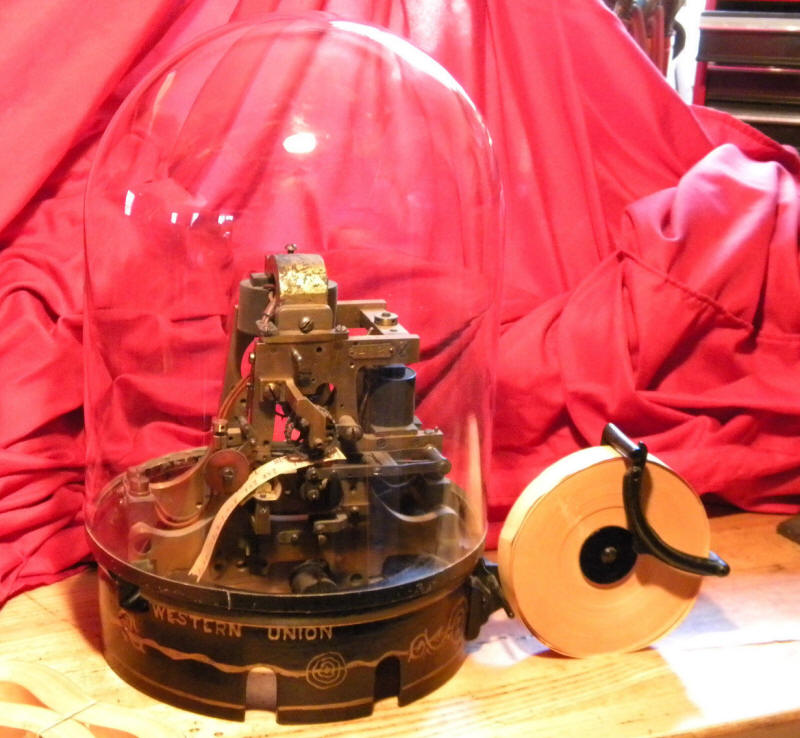

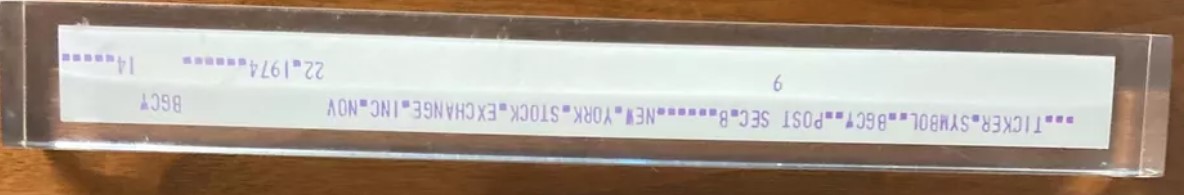

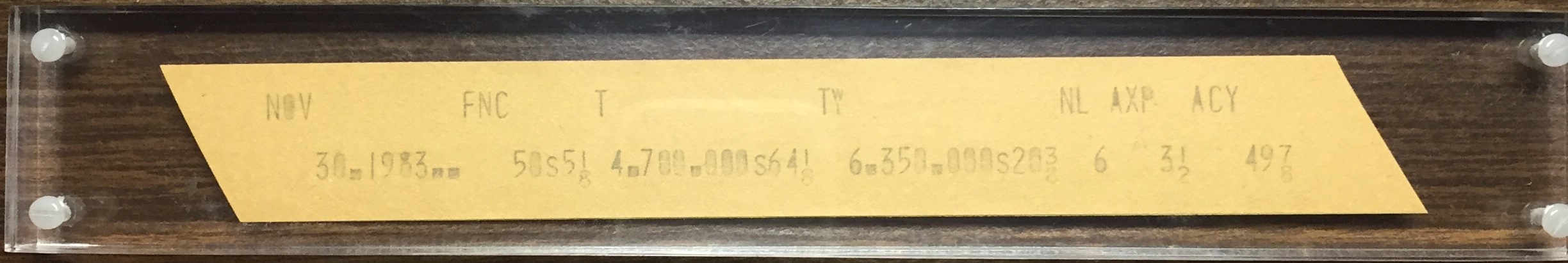

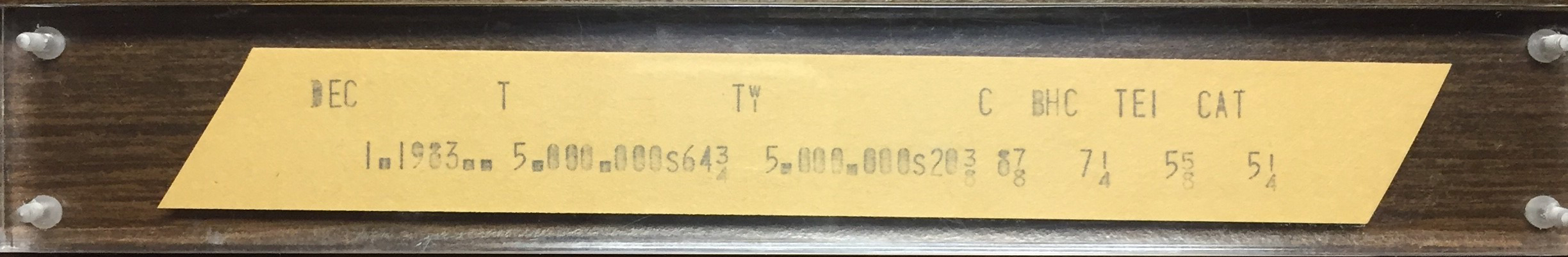

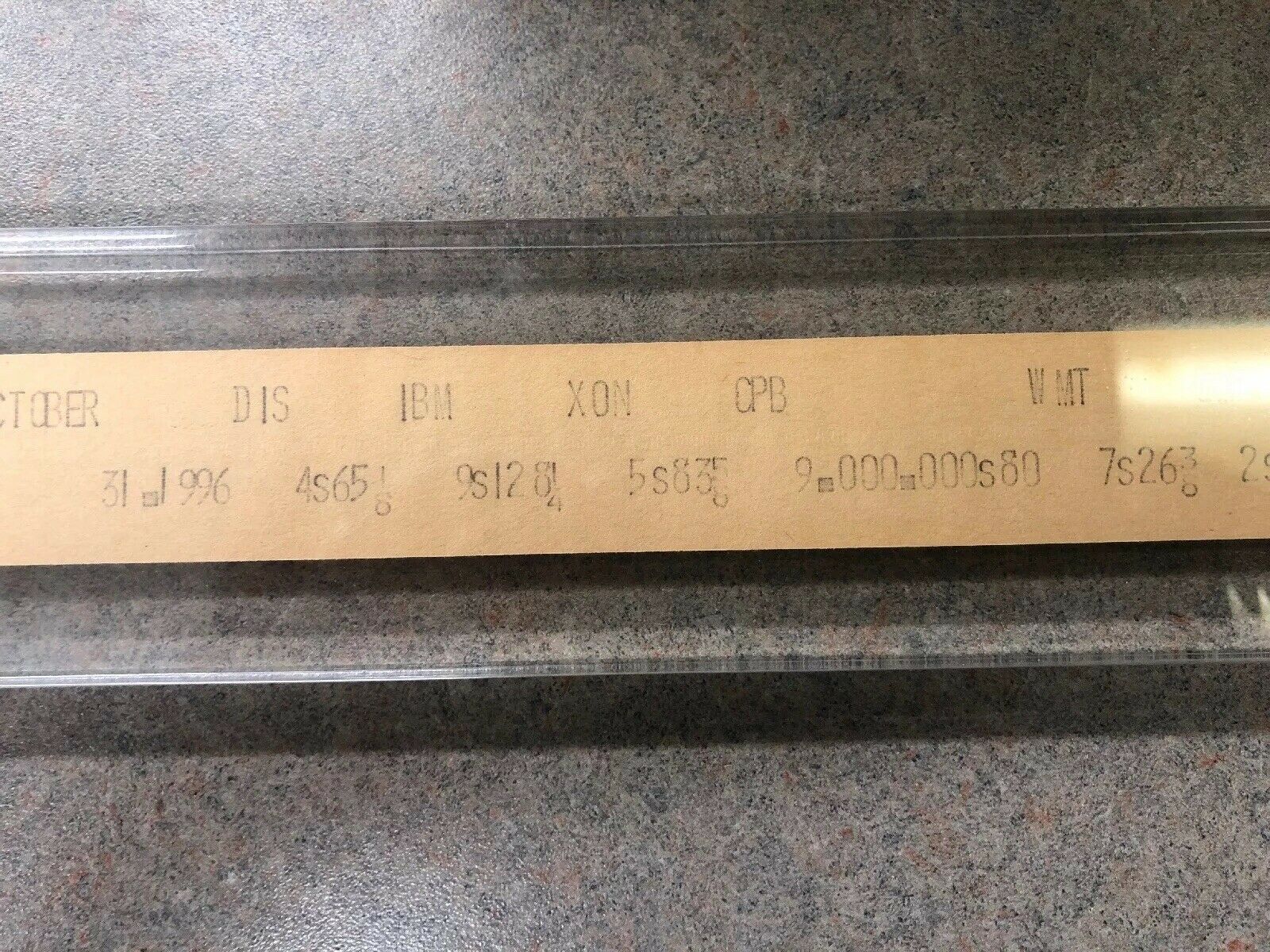

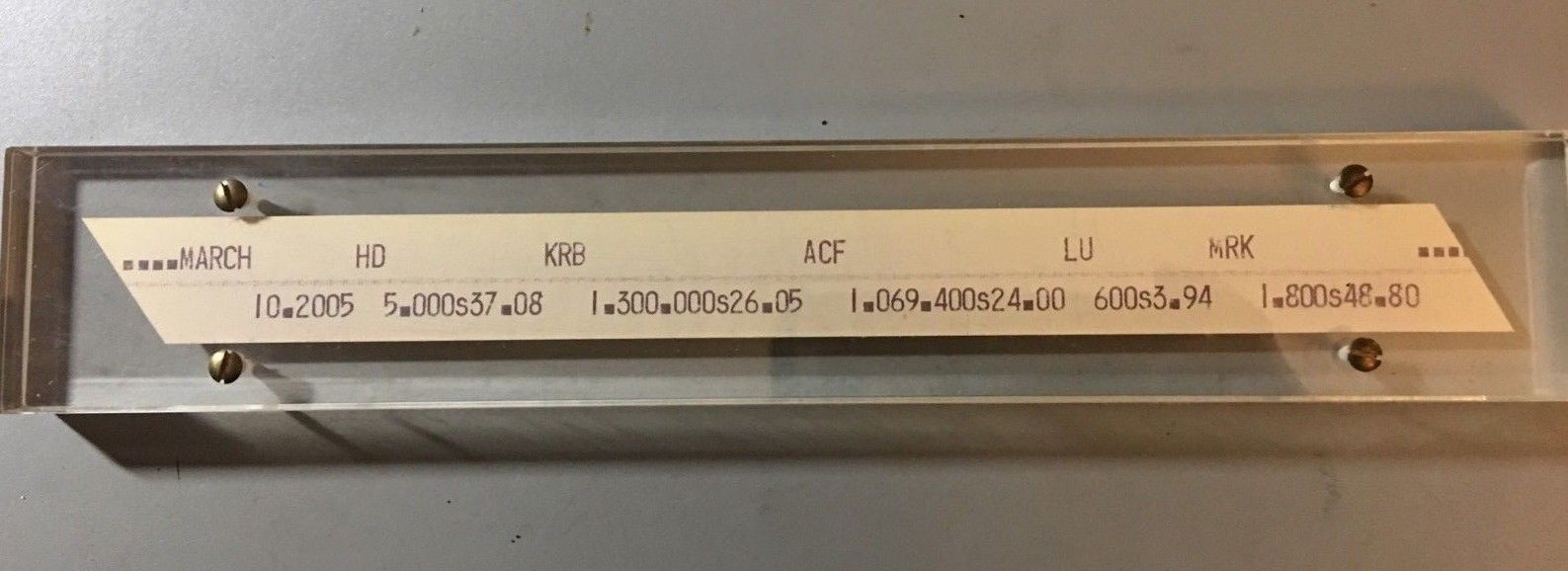

Rusty suggested that this ticker machine would have been in the broker's front office because some, perhaps older,

customers expected to see a ticker machine in a

brokerage office. Also, it added a little noise to the office which gave an air of busy-ness. Also, some of the older

brokers had lived with ticker machines all their lives, and did not want to give them up. Note that the following day,

Friday April 1, 1994, was an exchange holiday for Good Friday. I suggested to the vendor that someone knew they were going to have a

long weekend, they felt relaxed about it, and they grabbed the tape to take home for their kids to play with, or

just for fun, or something like that. Alternatively, perhaps the analog data feed was being discontinued at the

end of the first quarter of 1994, and this was the last day that the ticker machines ran.

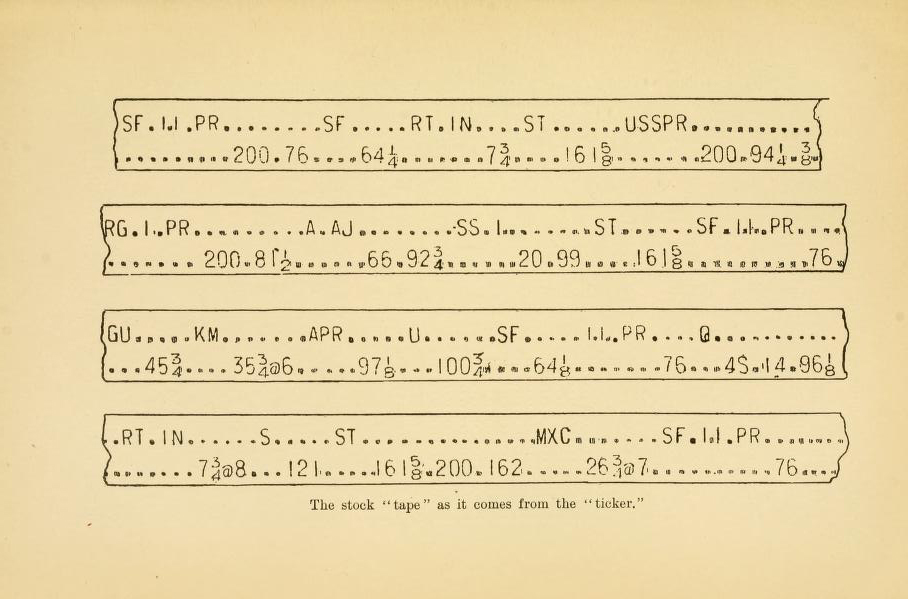

| How to Read Ticker Tape |

This section is based on multiple sources, including Barron's Dictionary of Finance and Investment Terms (2003), and Barron's Finance and Investment Handbook (2003).

| More Ticker Tape History |

Let me take a moment to compare ticker tape collecting to postage stamp collecting. Adhesive paper postage stamps were first used in 1840, 27 years before New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) ticker tape was first used, in 1867. Stock ticker machines started to be retired in the late 1960s, but they did not stop running completely until 1994. So far, postage stamps have outlived the ticker's demise by roughly the same three decades that they predated its birth.

Unlike ticker tape, postage stamps were printed in advance of being used, then typically affixed to an envelope or package, and then subsequently mailed to some recipient. So, their life had multiple stages over some period of time: design, creation, affixion, and delivery. Each stamp is a mini work of art, often framed in its own perforated border. Stamps cry out to be collected! If they were larger, you could hang them on your wall. (In fact, I do have several framed stamps on my walls.) In November 2022, I looked at eBay.com and saw over 11,000 "postage stamp" listings, ranging from about $1 to about $7,000. An advertisement from Hipstamp.com in the July 2023 issue of The American Philatelist claims they have 7 million+ stamps from 1,200+ sellers. As a consequence, anyone can amass an interesting and diverse collection of attractive stamps at prices to suit their budget. Many stamps are common, some are rare, and some are exceedingly rare. Stamp collections are as varied and interesting as the collectors themselves.

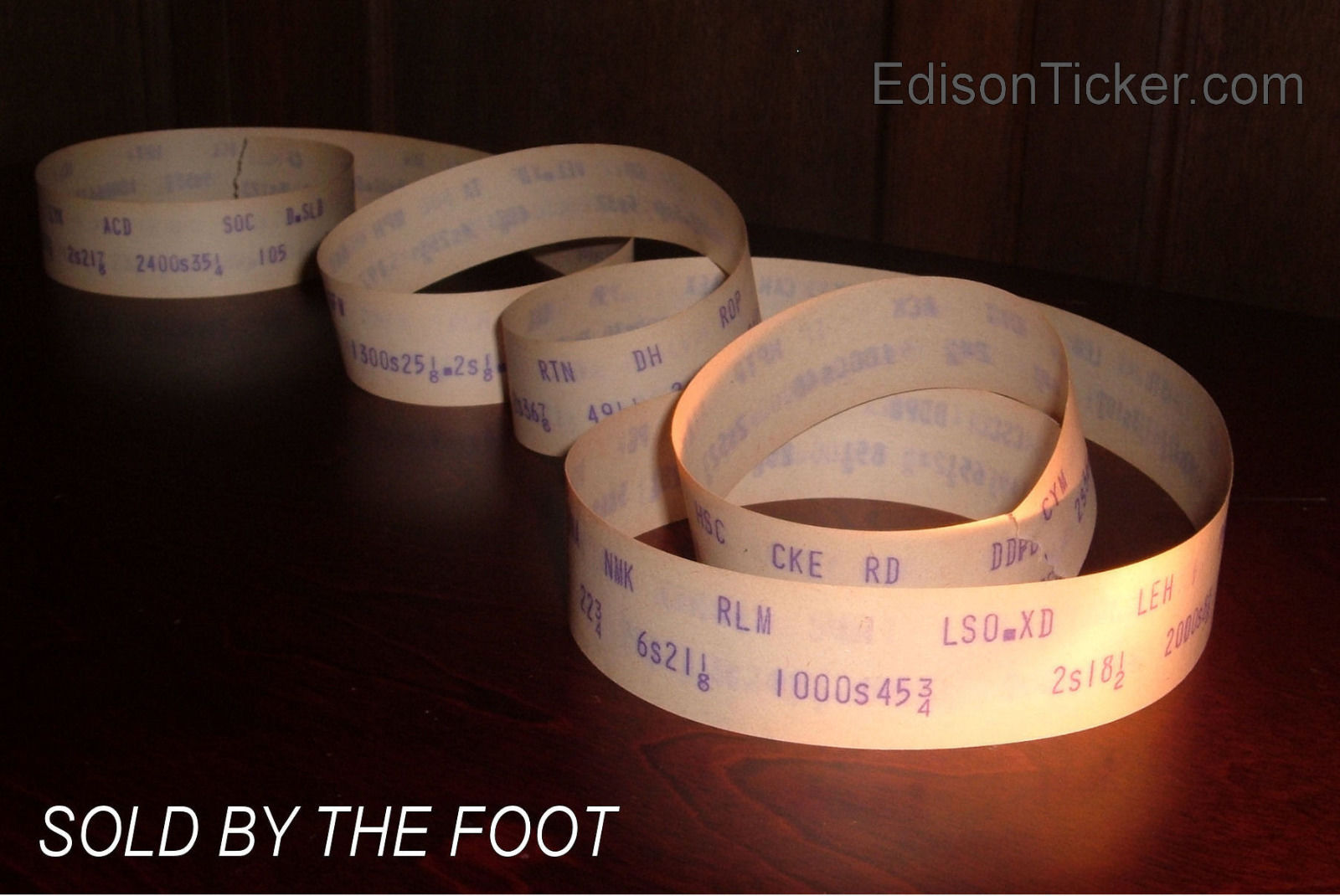

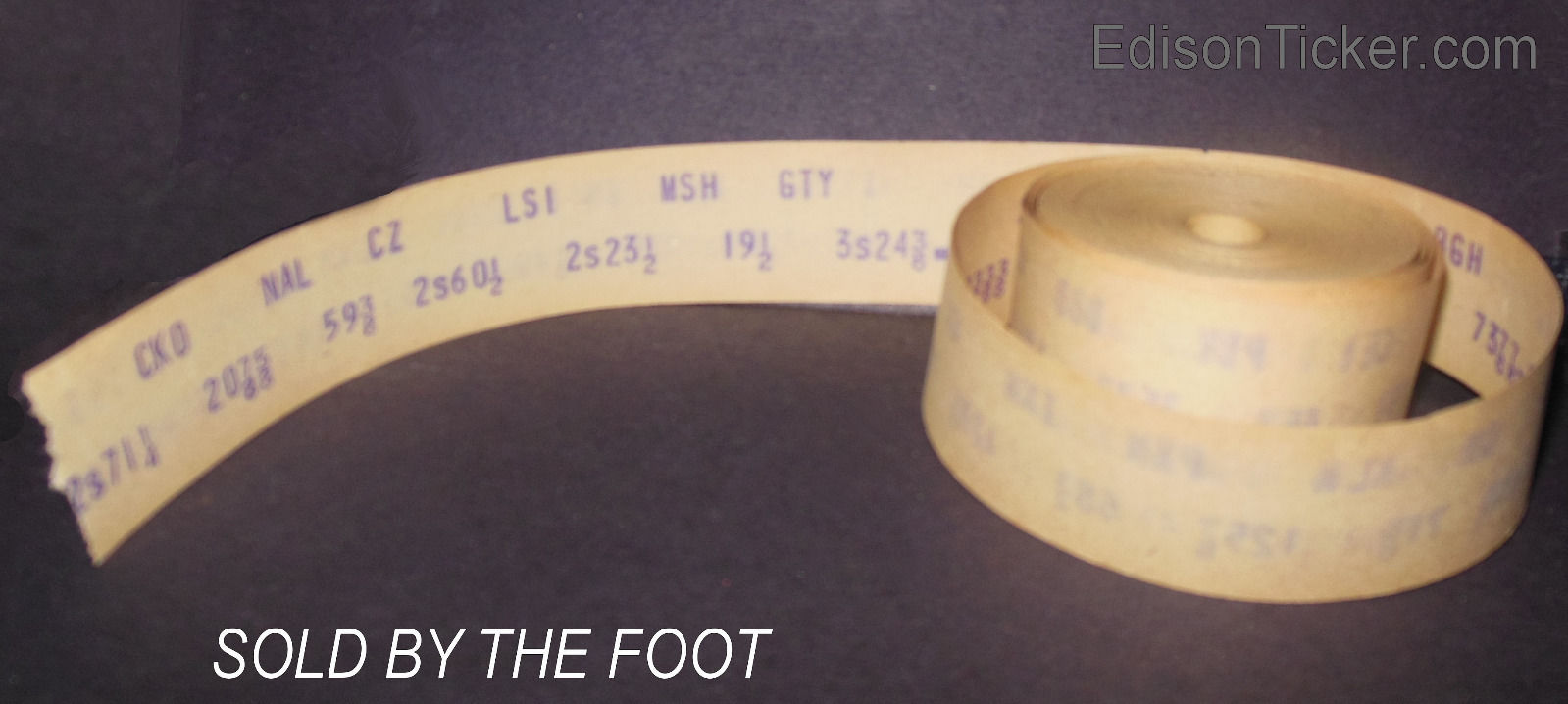

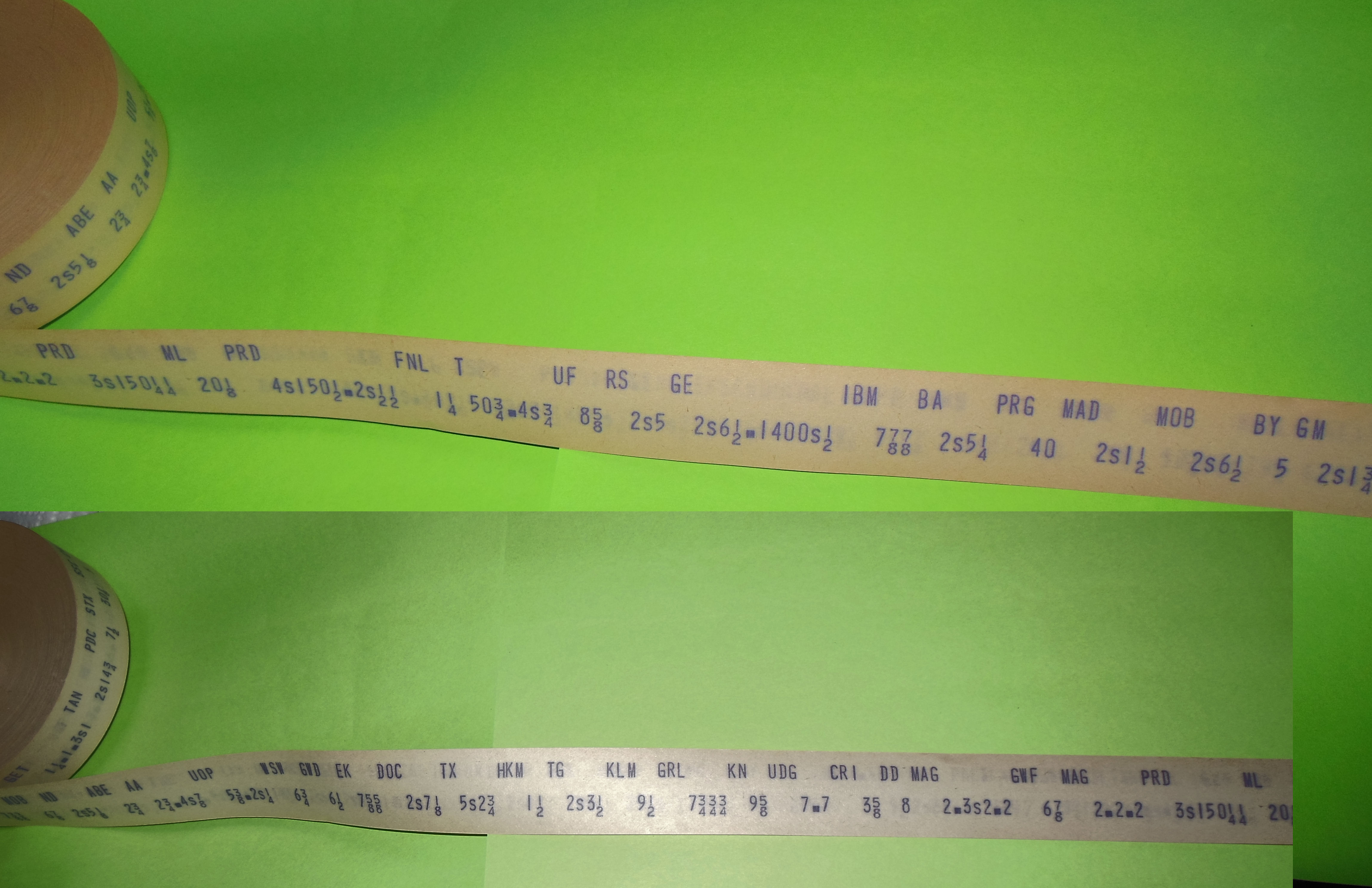

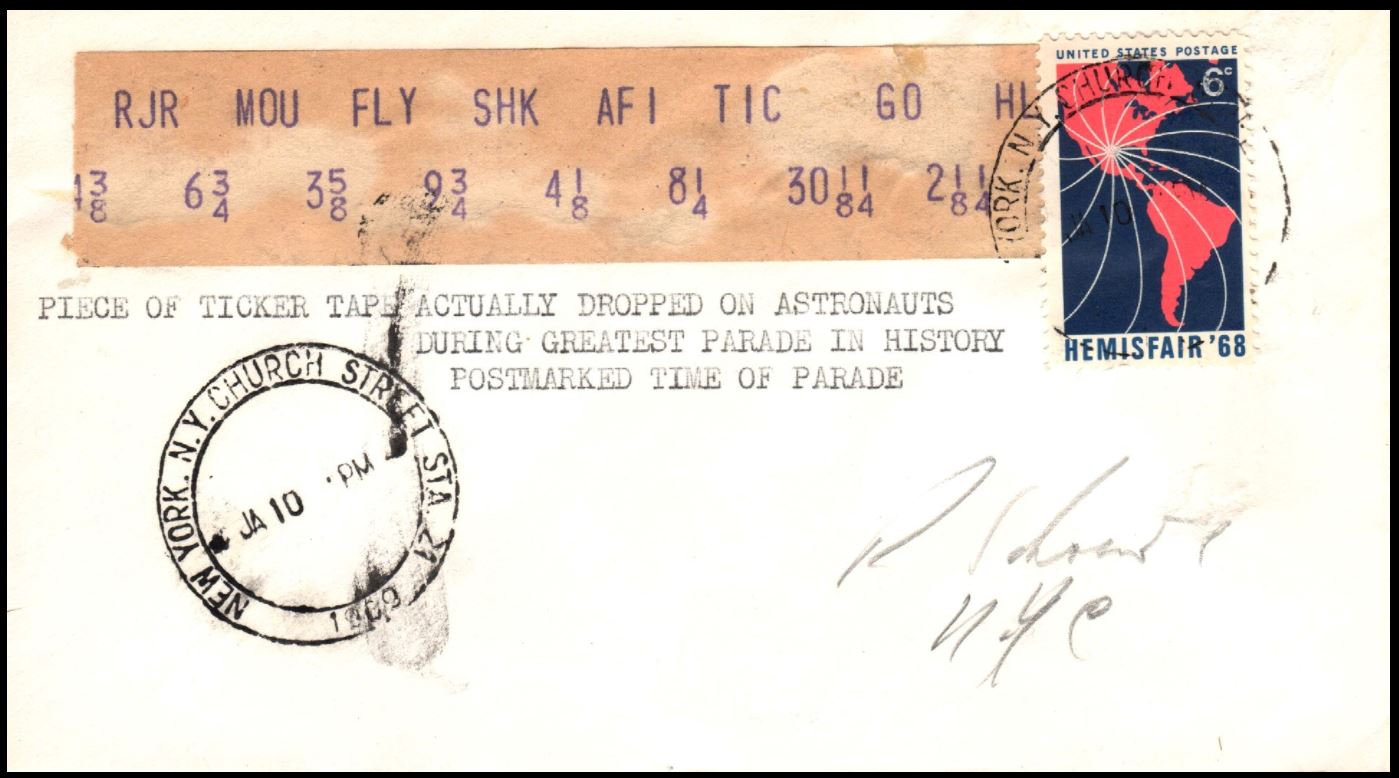

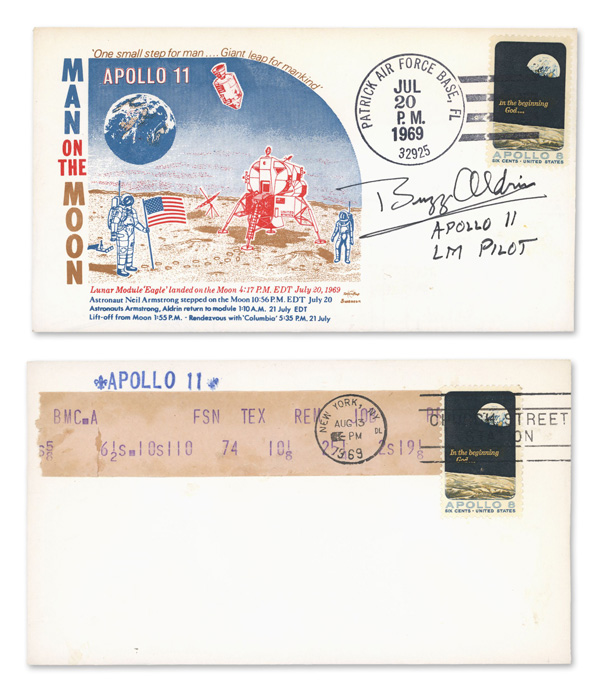

Unlike stamps, however, ticker tape was printed on the cheapest possible paper, immediately viewed, and then discarded. It was stale and useless by day's end, and had little further use (except perhaps to be thrown during a parade if it had not already been thrown in the trash). Although I estimated above that 100 million miles of ticker tape was printed between 1867 and 1994, finding ticker tape nowadays is difficult. I look at eBay.com about once a week, but 99 times out of 100 there is no genuine printed NYSE ticker tape for sale. In terms of scarcity, genuine NYSE printed ticker tape is like an exceedingly rare stamp. After 20+ years of collecting, I have managed to amass a collection consisting of exactly one piece of NYSE ticker tape. Can you call it a collection if you have only one piece?

It took some time for me to realize that printed NYSE ticker tape is so rare that being a collector of it is a futile hobby. So futile, in fact, that demand for ticker tape from the general public is negligibly low. Low demand means, in turn, that you might buy a foot of unremarkable NYSE printed ticker tape for $20—if you can find it. In this regard, unremarkable NYSE printed ticker tape is unlike an exceedingly rare stamp: it can be both exceedingly rare and inexpensive because the demand is so low. (There are exceptions, like the $5,000 ticker tape from the crash of 1929 mentioned above, but that is remarkable tape, not unremarkable tape.) Given the futility, I gave up collecting ticker tape, and chose instead to collect ticker tape images. Now I have a collection! A byproduct of my collection and my interest is that I often end up helping the few ticker tape owners out there who do exist (and who, like me, often also have amassed a one-piece collection).

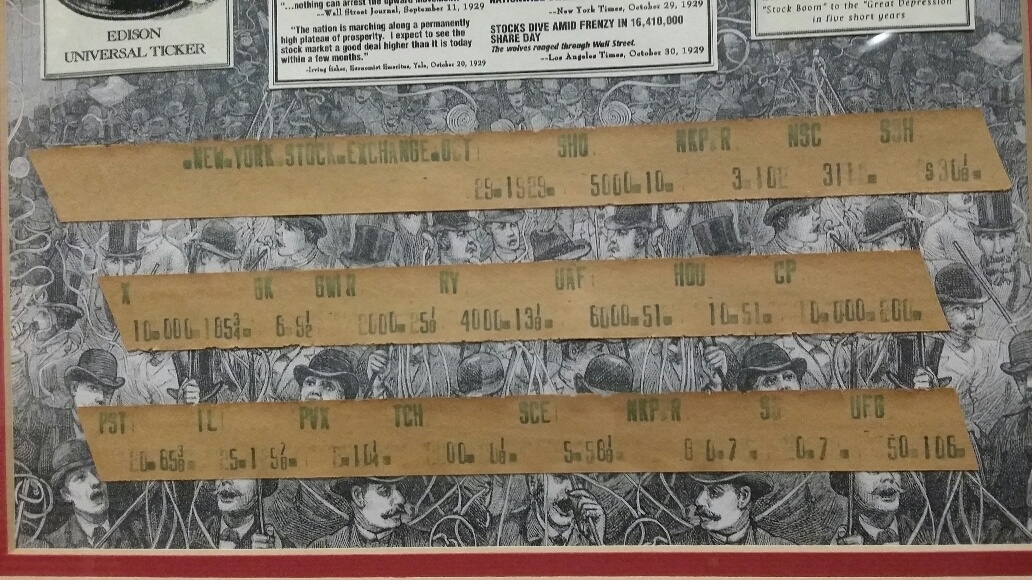

Let me add that I find ticker tape fragments interesting because even the shortest snippet is a vignette that tells a story about that day's trade. Oftentimes, that piece of tape was set aside for a reason. Maybe it was an important day in financial history (e.g., the October 29, 1929 snippets), an unusually busy day in the market (e.g., the March 9, 1961 snippet), or a personal visit to the NYSE (April 15, 1965 snippet). Alternatively, maybe it was incorporated into something else (e.g., the pin/ash trays and jewelry box from 1967 and 1968), or the ticker tape parade envelopes from the 1960s. I guess the same is true of stamped envelopes or cards that were mailed to someone, though it's not necessarily true of unused stamps.

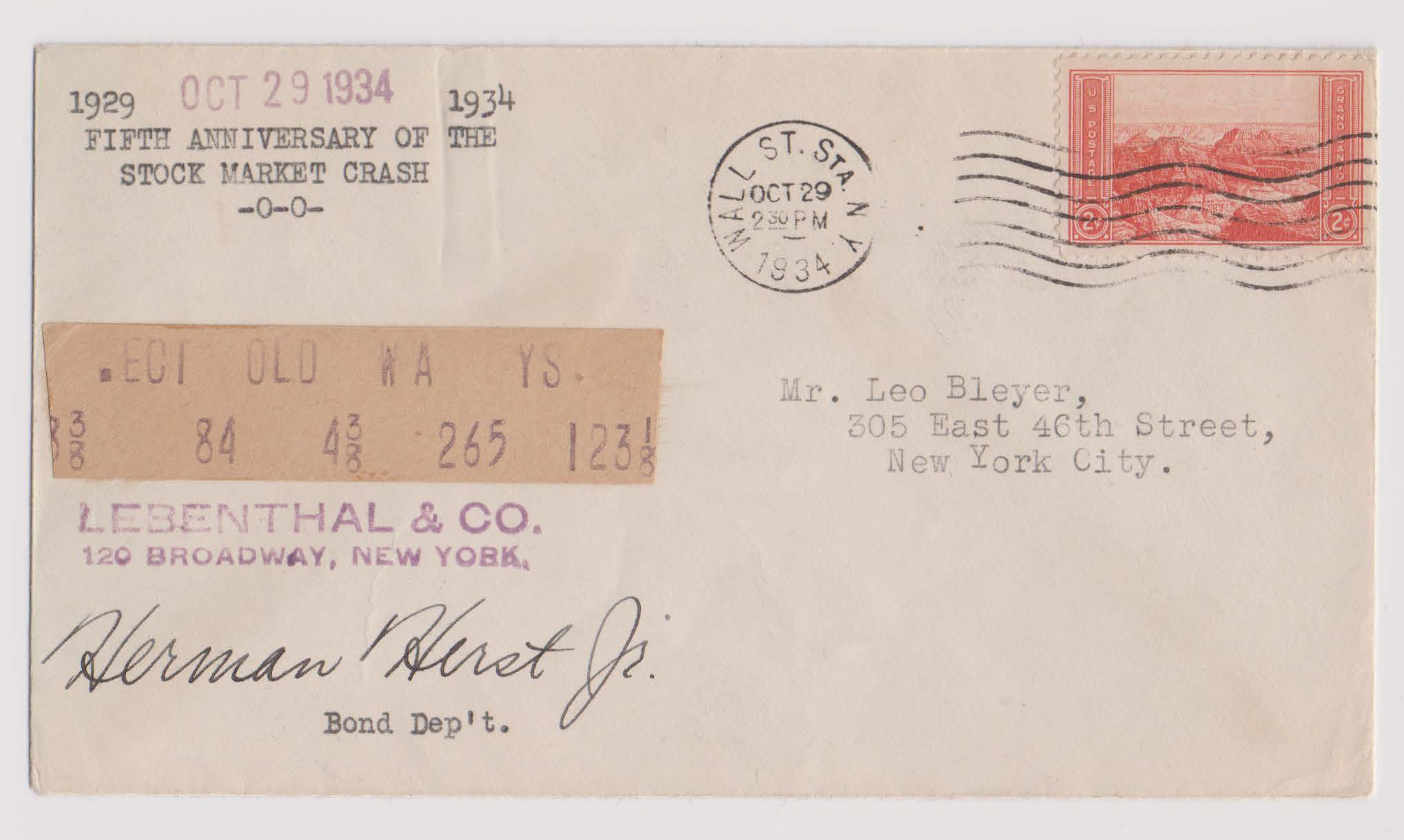

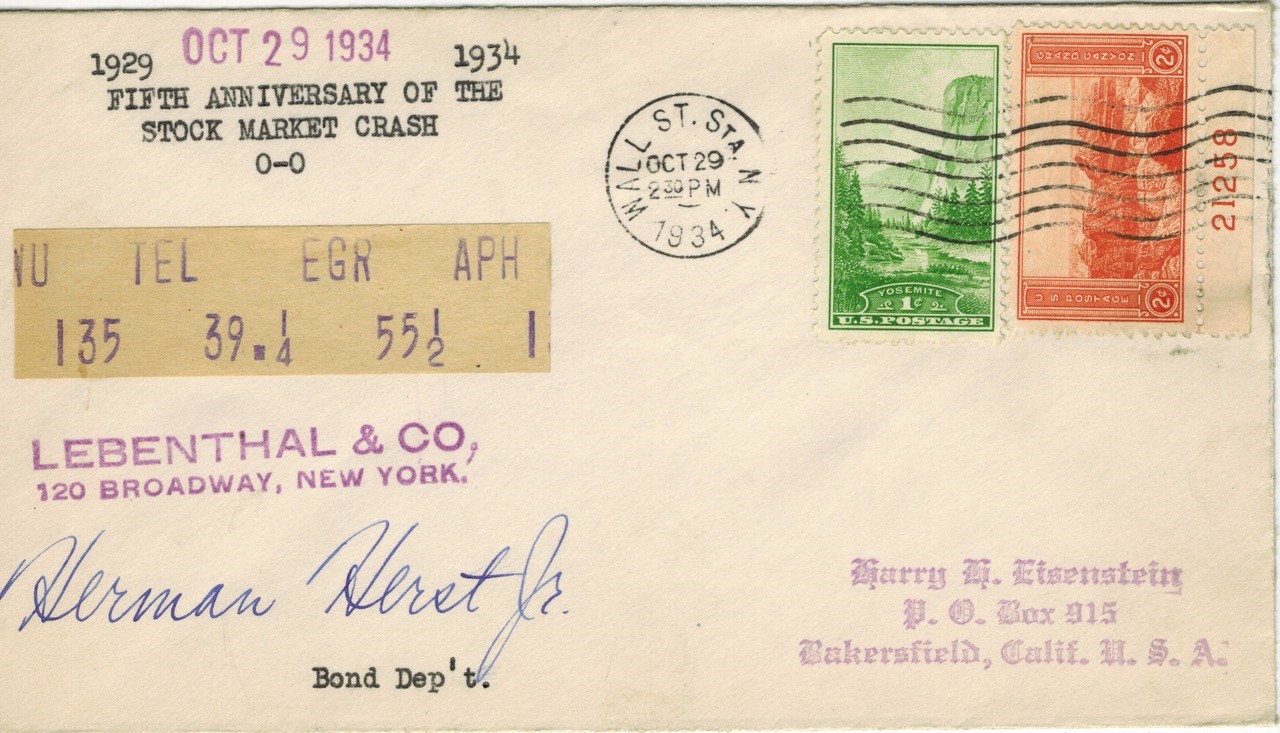

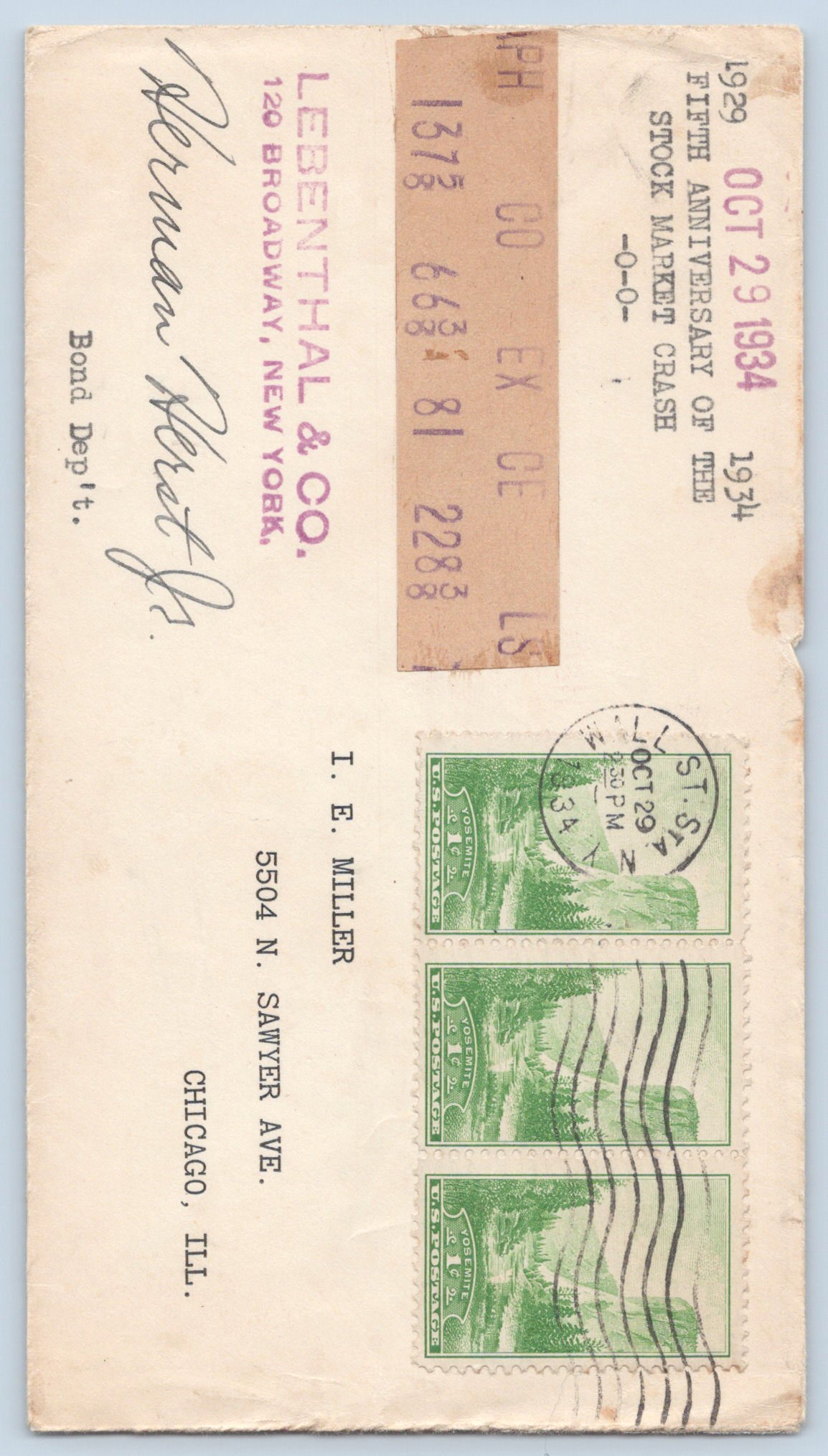

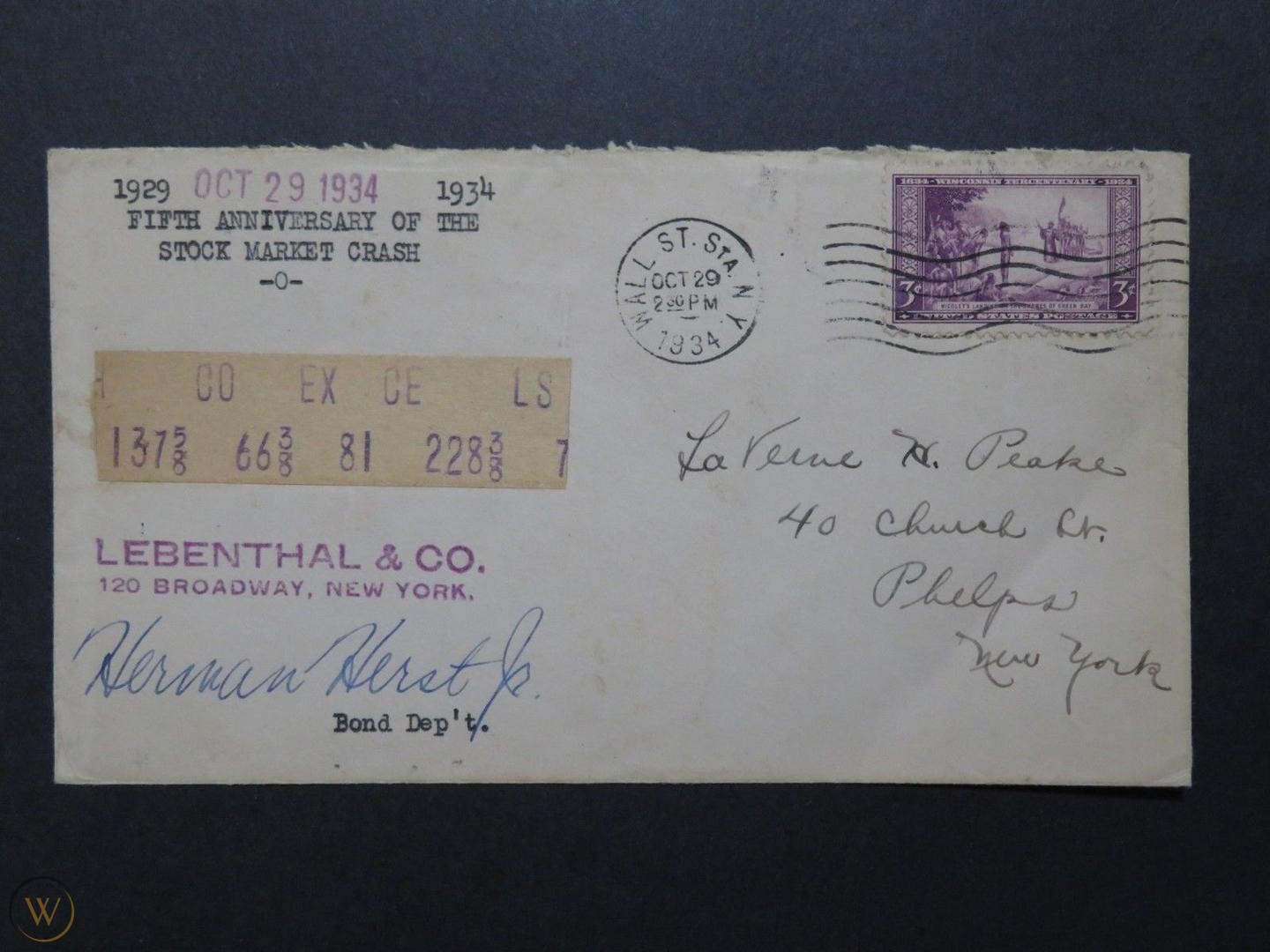

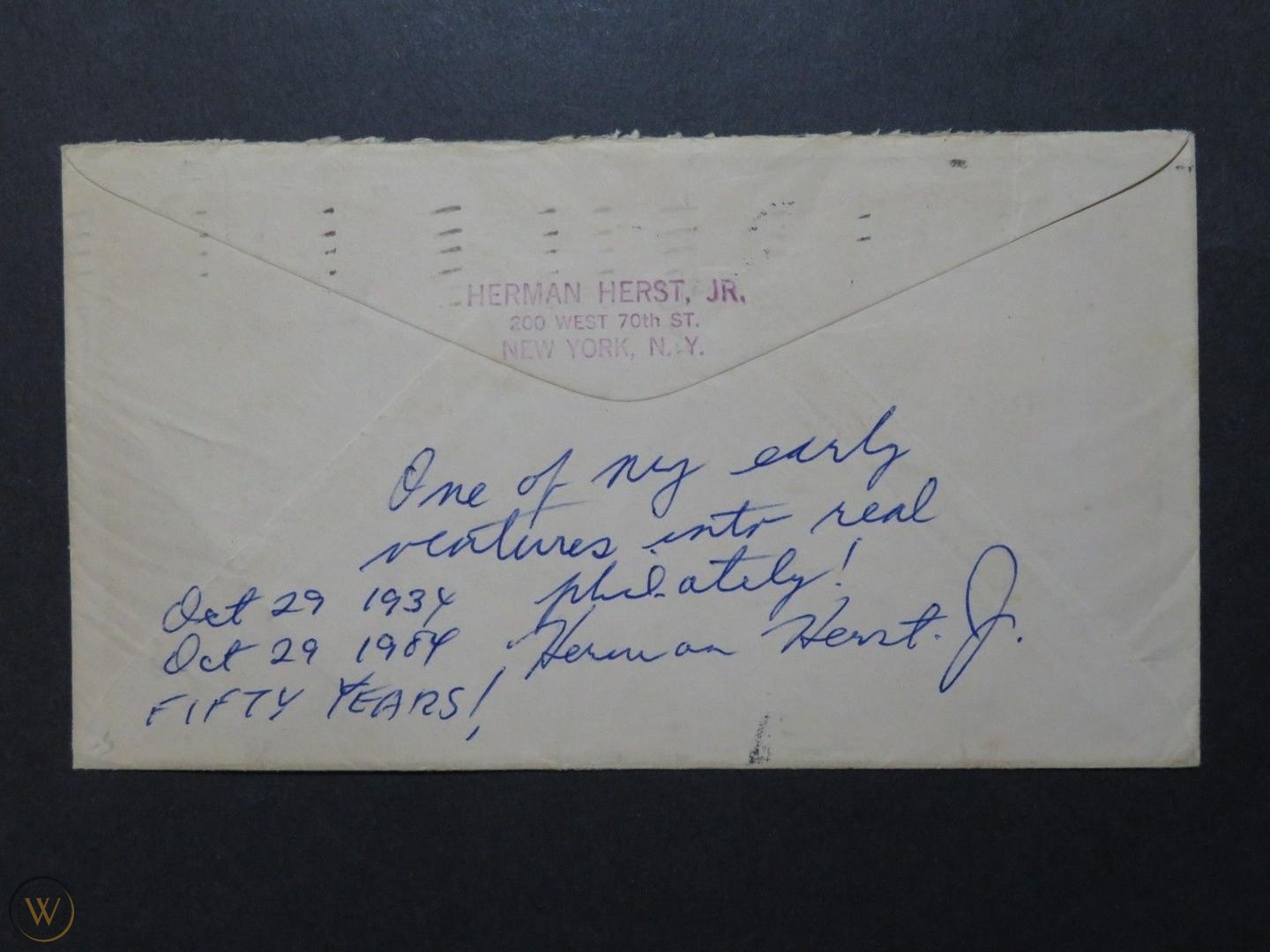

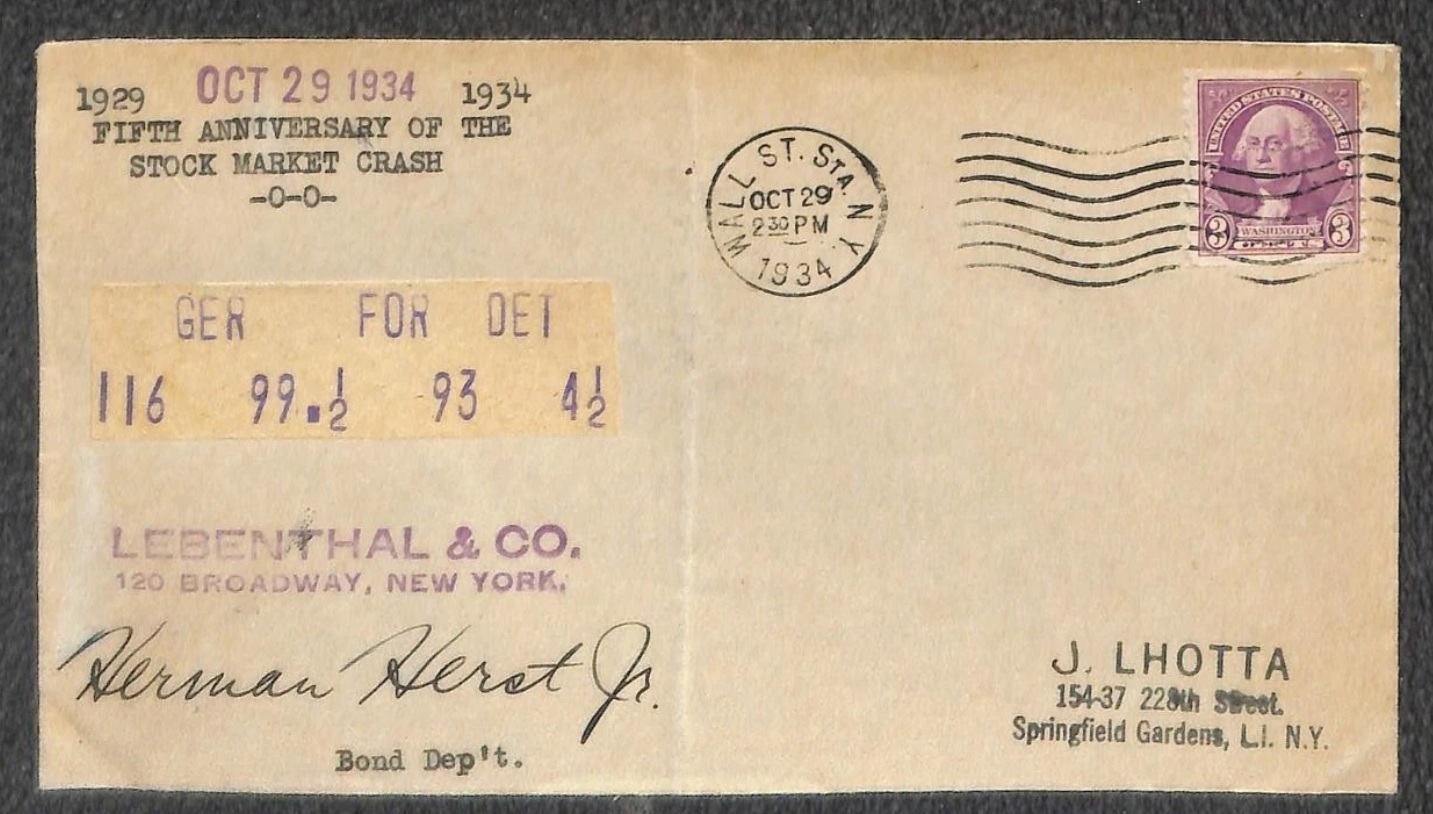

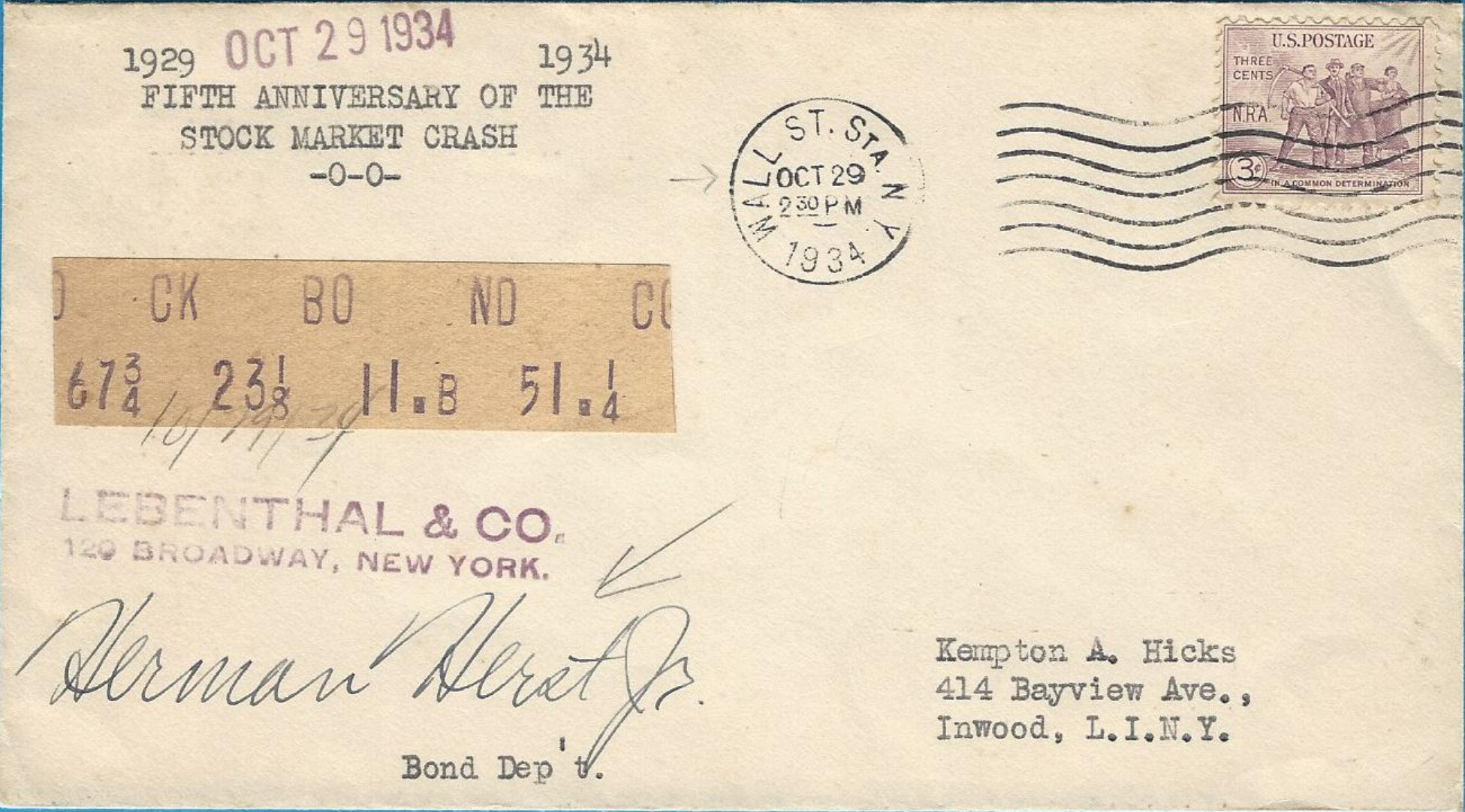

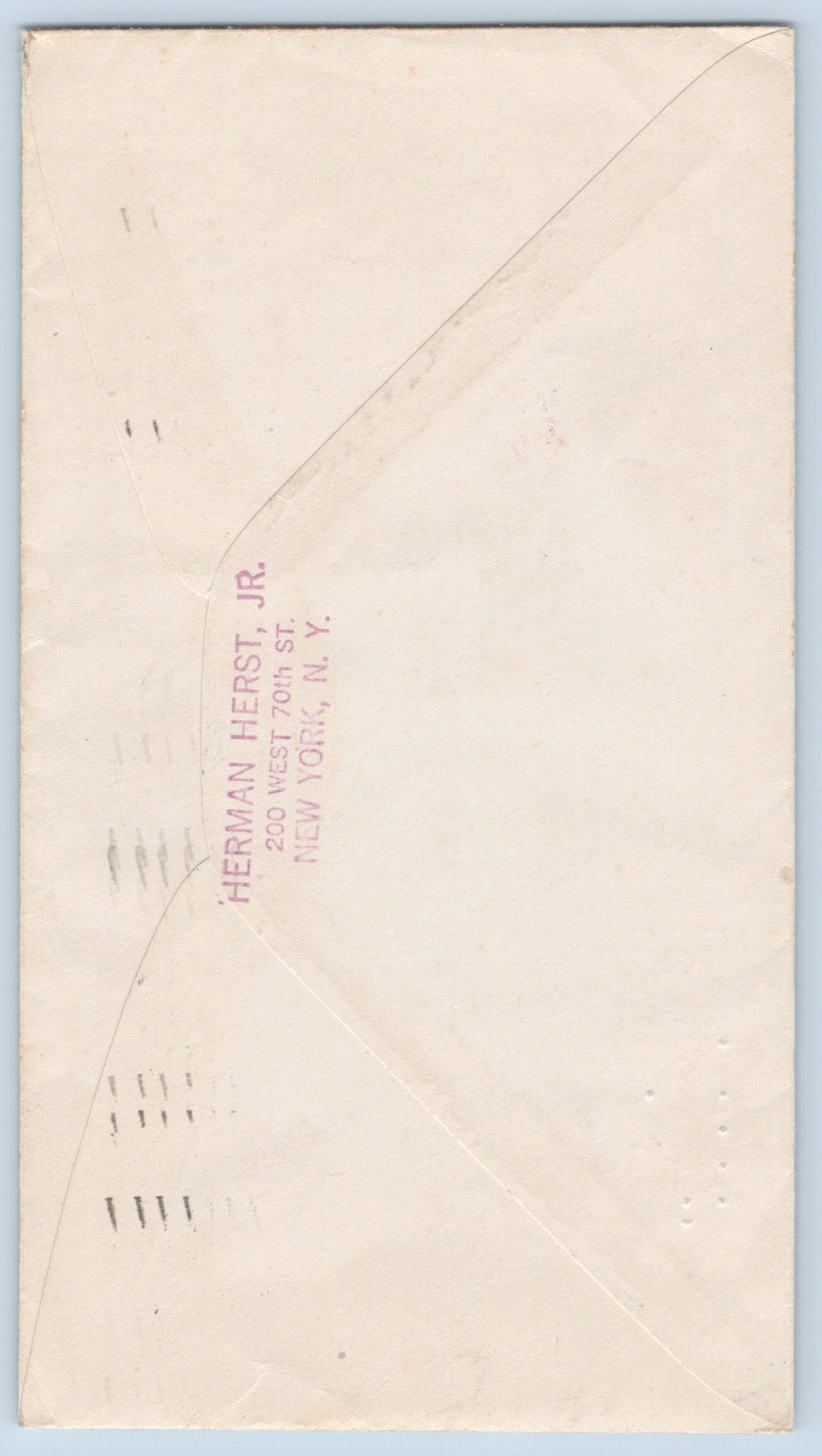

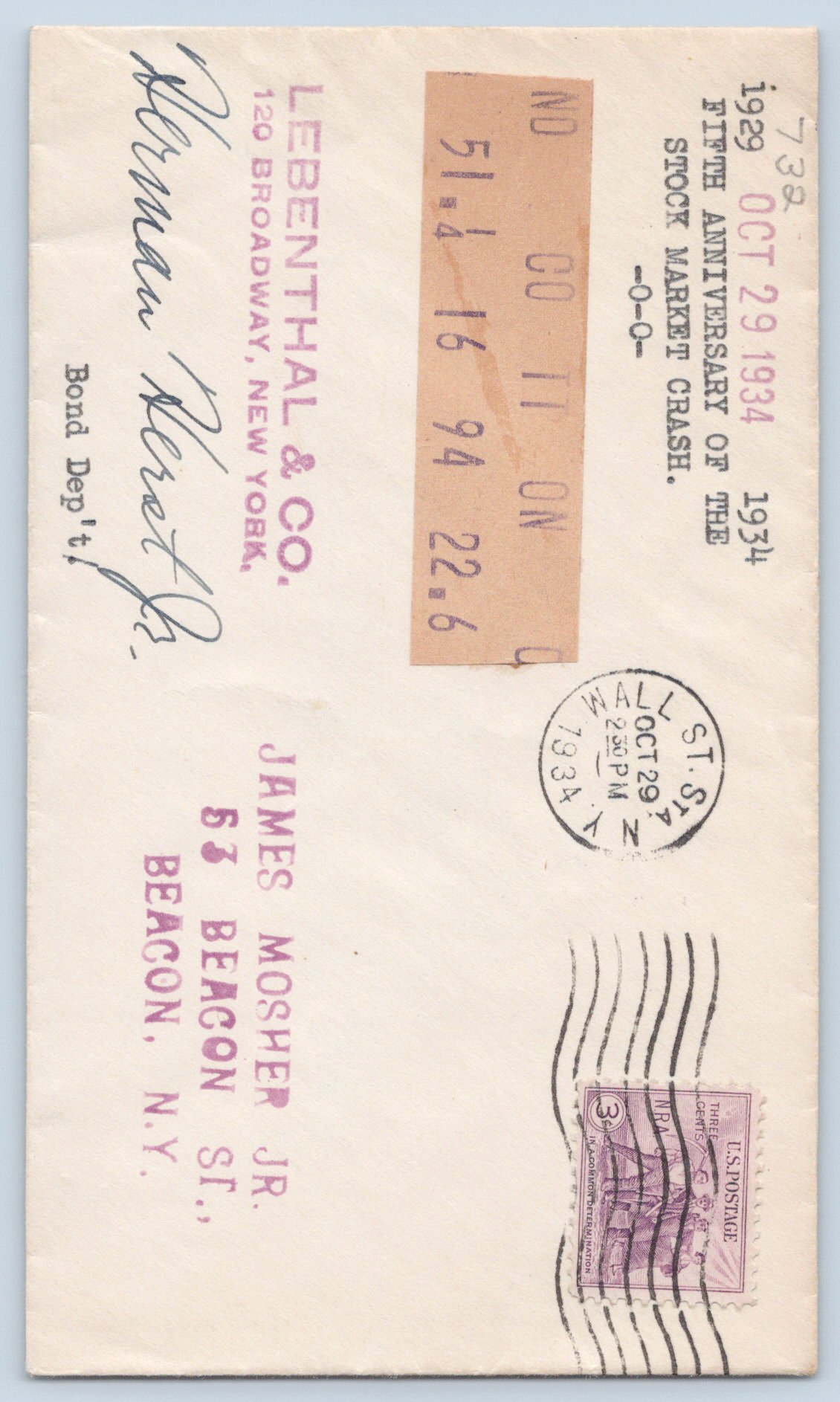

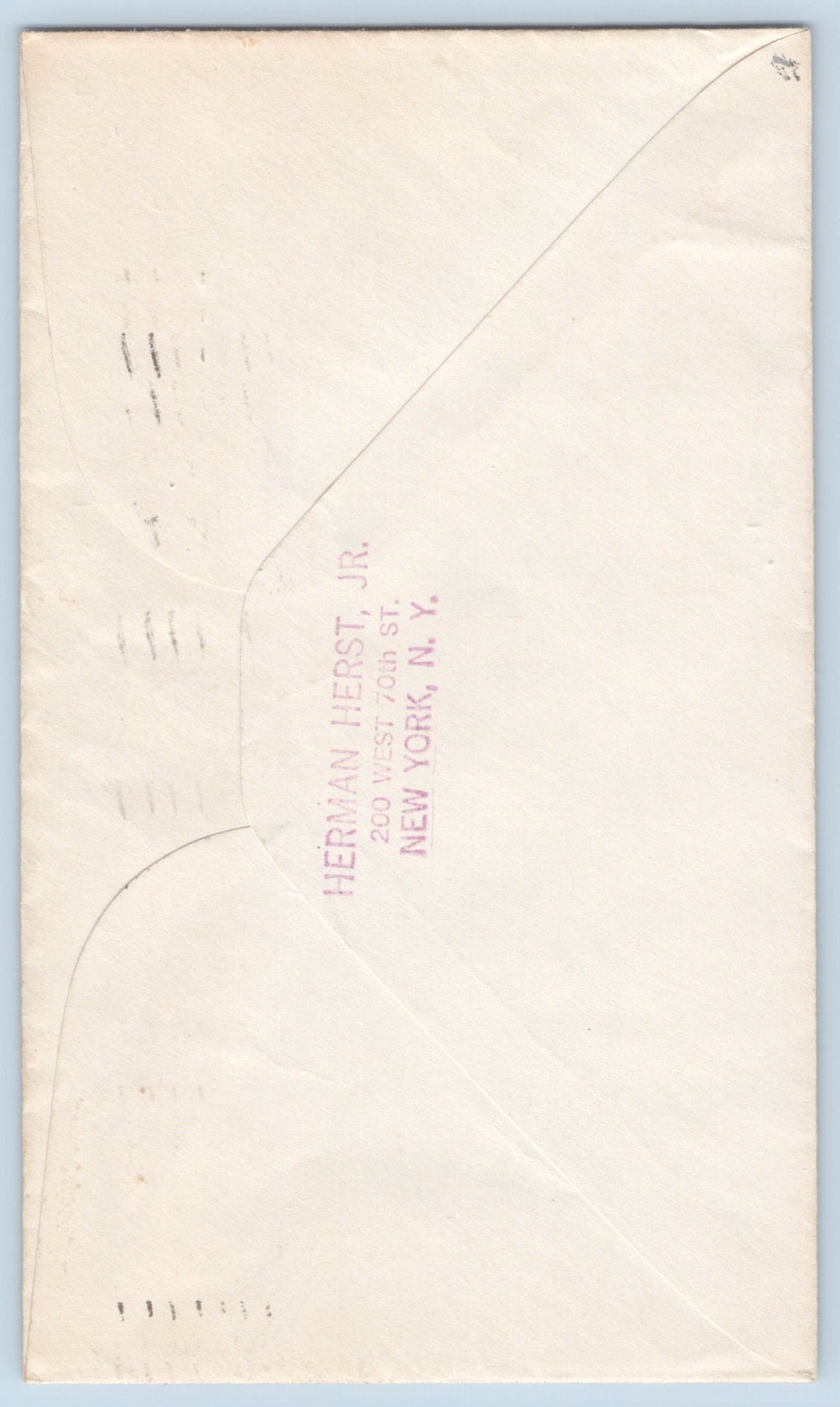

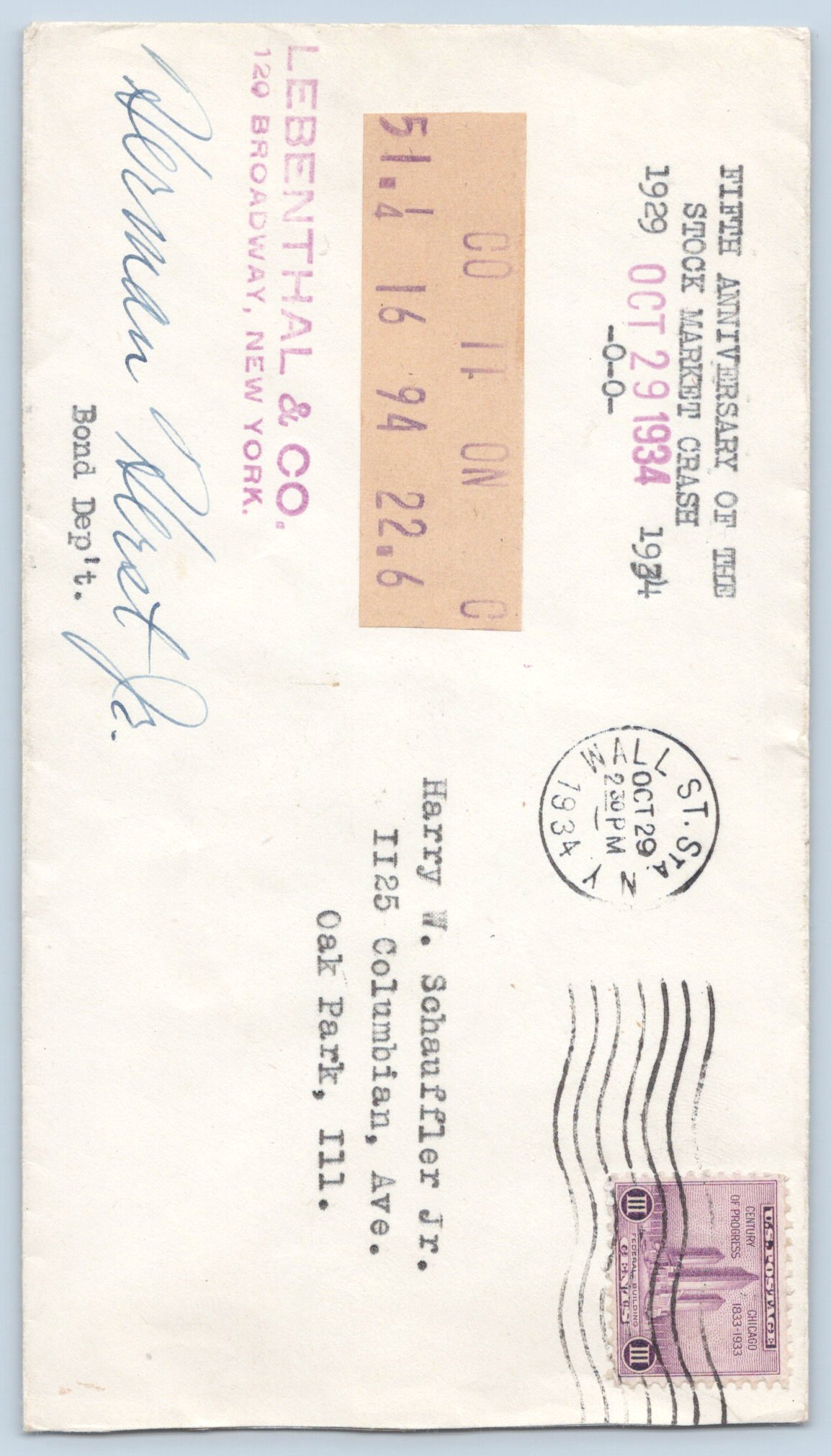

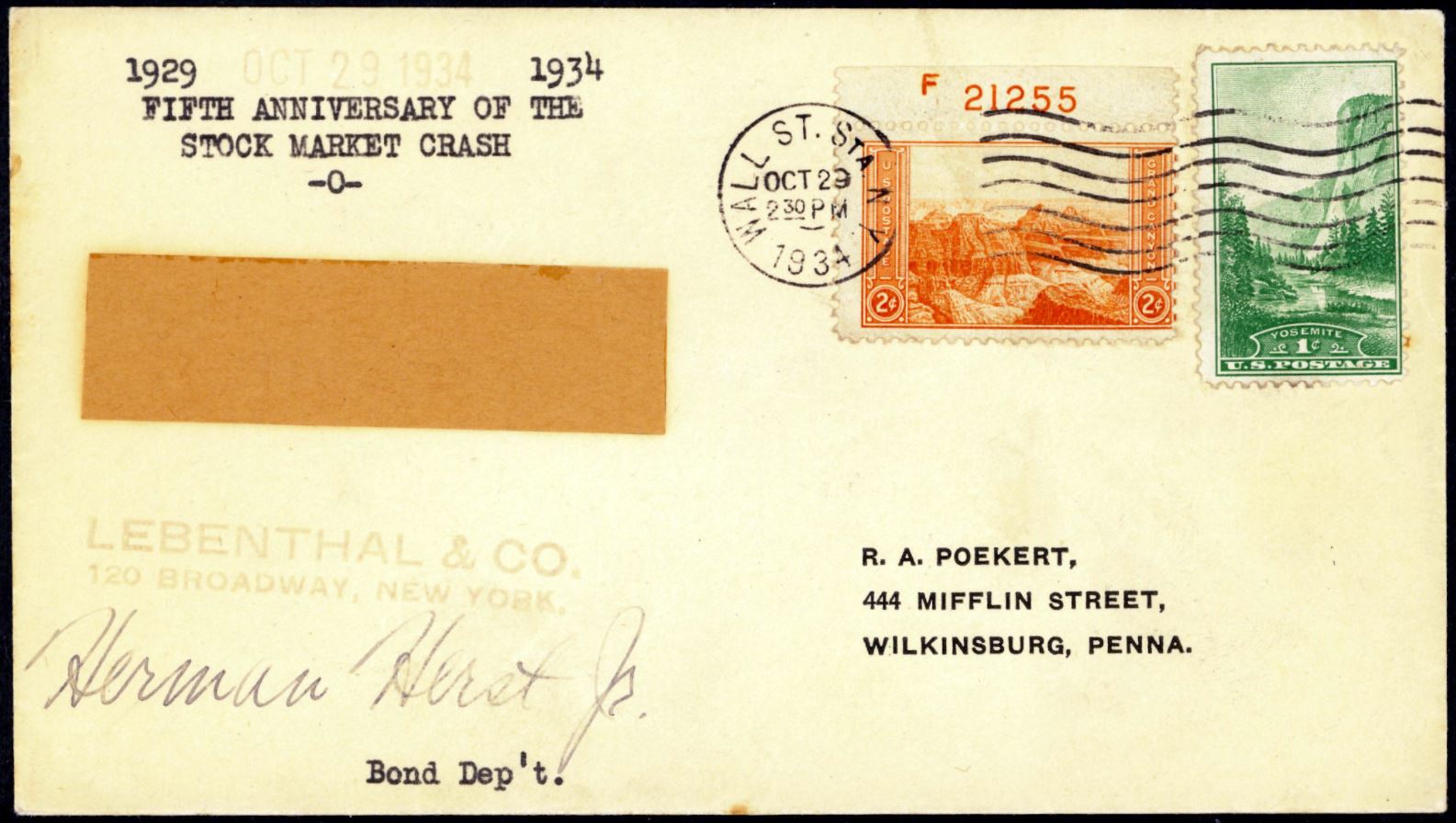

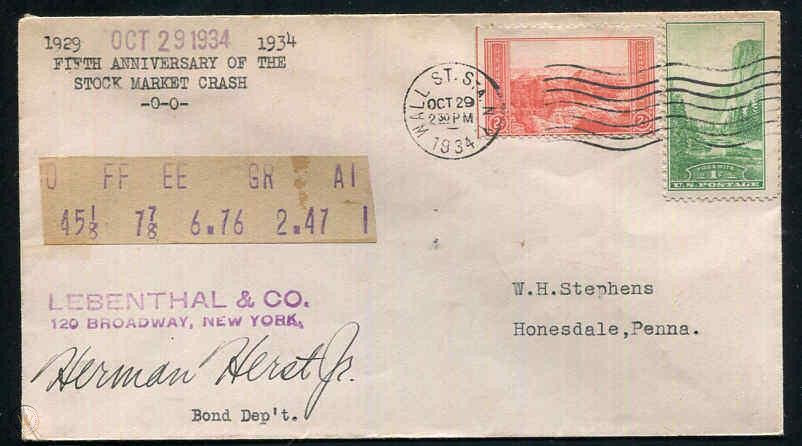

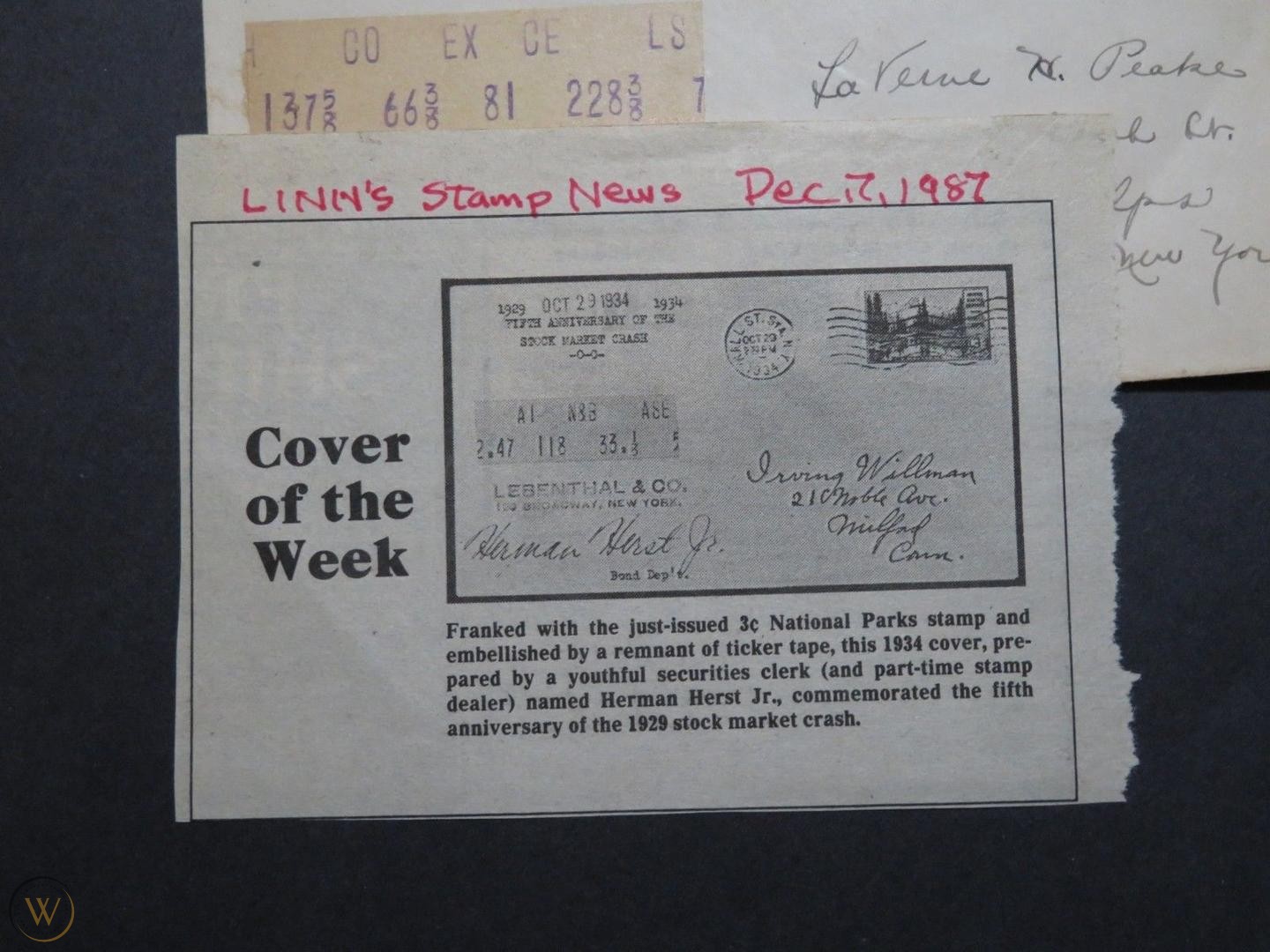

The commemorative philatelic covers displayed below have stock ticker tape pasted onto them. They were constructed and then mailed as we see them on the afternoon of Monday October 29, 1934. So, they are at least that old. They mark five years since Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929. I think that each item was made up by Herst personally (typed, ticker tape pasted, stamped with the company name, etc.) and I believe that they were mailed personally by him at Wall Street Station Post Office near his office.

Given the different forms of address (typed, stamped, handwritten), I think Herst used stamped self-addressed envelopes sent in by collectors. (Thank you to Olaf Rappe for this observation.)

Let me describe what the various stock ticker symbols represent on these pasted tape snippets. It is, however, somewhat of a moot point, because they are almost certainly fabrications. In fact, these are the earliest fabrications I have seen. Herman Herst is playing a prank on us from the grave. (I do wonder whether Herst was trying to create a new collectable genre, with his prank ticker tape.) As far as I can tell, Herst's prank remained hidden for 88 years, from 1934 to 2022, as I will explain.

Note that Herst could use no more than about 10-12 characters to write a message, but he often used half that number. It's difficult to say much in so few characters. So, his pranks are pranks in only two dimensions: they are not what they purport to be (i.e., they are not the natural product of NYSE trading); and, they contain hidden messages.

The ticker symbols appearing: ECT is Electric Storage Battery Corp., YS is Youngstown Sheet and Tube Corp., WU is Western Union, TEL is Telautograph*, CK is Collins and Aikman, BO is Baltimore and Ohio RR, ND is National Dairy Products Corp. (now under Kraft), WA is Wabash RR, CE is Chicago and Eastern Illinois RR, BR is BF Goodrich. CO is the Chesapeake and Ohio RR. To the best of my knowledge, however, the other symbols on these tapes (OLD, EGR, APH, EX, LS, FF, EE, AI, ASE) do not correspond to any actual stocks trading in 1929 or 1934, though some of these symbols were used later by the NYSE.

*The Telautograph was invented in 1888. It was the first machine that allowed a picture/signature/handwriting to be transmitted via electrical signals to a stationary sheet of paper. It was, in essence, an early fax machine.

Daniel Schibley, an amateur philatelist in the U.S., showed me the WU TEL EGR APH envelope in October of 2022. He pointed out that the last three symbols spell TELEGRAPH when combined, and he asked me about it. Up to that point I had seen the ECT OLD WA YS cover (courtesy of Olaf Rappe in 2021) and the CK BO ND CO cover, and I had not noticed the pattern or realized that Herst was playing a joke on us. For one full year prior, I had puzzled over the prints I had seen. They showed phantom ticker symbols alongside ticker symbols that purported to be from October 28, 1929, as follows.

WU TELEGRAPH is Western Union Telegraph (note, however, that the Trans-Lux Directory mentioned above lists Western Union simply as W: UEL–ZP). I suspect that ECT OLD WA YS is PRO T [ECT OLD WAYS] or CO NN [ECT OLD WAYS]. I see now that CK BO ND CO is STO [CK BOND CO] T TON. There is also CO EXCELS (where CO is for Chesapeake and Ohio RR, and the letter is addressed to Laverne Peake**), and there are envelopes with snippets of COFFEE GRAIN & BASE METALS, each of which is traded on futures markets: coffee, grain, and base metals.

**At first, I thought Mr. Peake was a fantasy created as a joke by Herst (i.e., that the Chesapeake RR prompted Herst to invent Mr. Peake). If Herst had mailed it to fake person, however, just to get it returned to him, then I would expect it to be stamped as "return to sender," which it is not. U.S. census records do indicate a man named Laverne Peake living in Phelps NY in 1940. According to the rear, Herst had this envelope in his hands 50 years later. Was he signing it for a collector who brought it in to him? I suspect that Herst's prank envelopes were all triggered by Mr. Peake's request for a commemorative envelope (with Herst noticing that he could use ticker tape to play with words using Peake's name).

Does any reader have a Herman Herst Jr prank ticker tape envelope from 1934 not pictured here? If so, please contact me: timcrack@alum.mit.edu. I am happy to help decode it. Your snippet of ticker tape might come from just before of just after one of the ones pictured here, and together they might help to explain each other.

I first suspected that Herst used some sort of test circuit to print these tapes, using some actual stock

prices from October 28, 1929, but also using made-up symbols that helped him spell out words, as a prank.

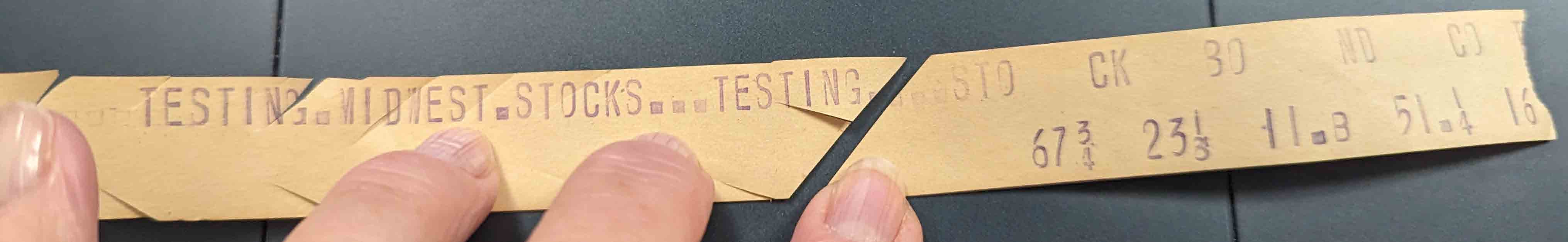

However, a viewer sent me a fragment of tape as follows:

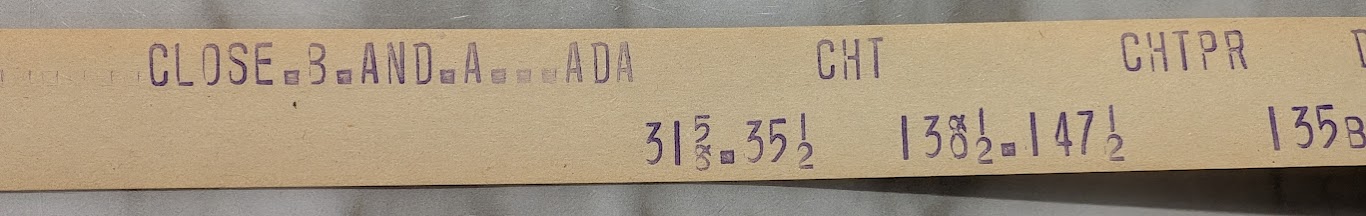

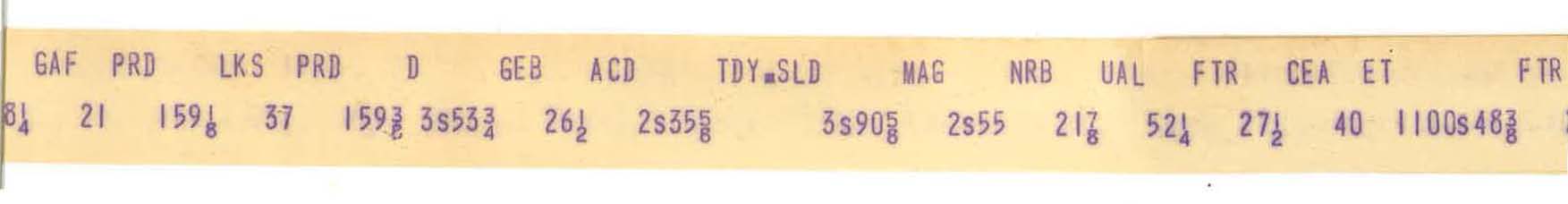

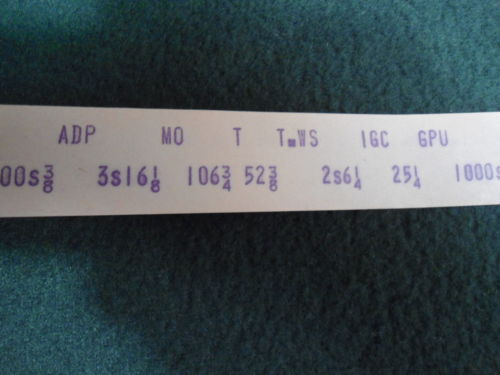

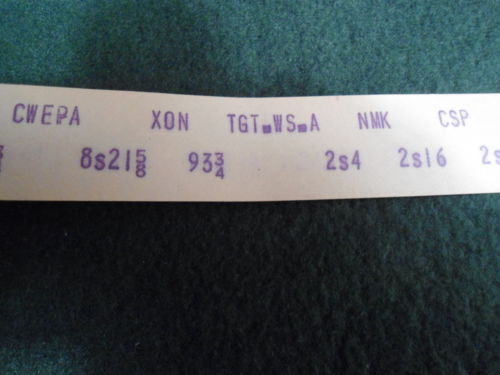

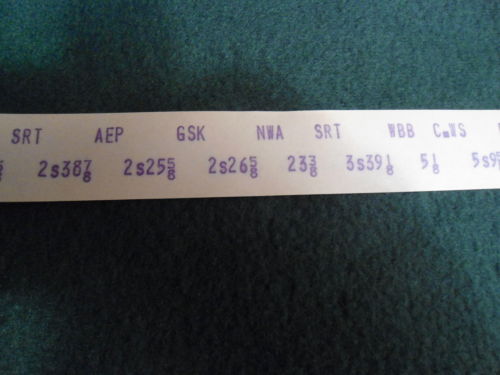

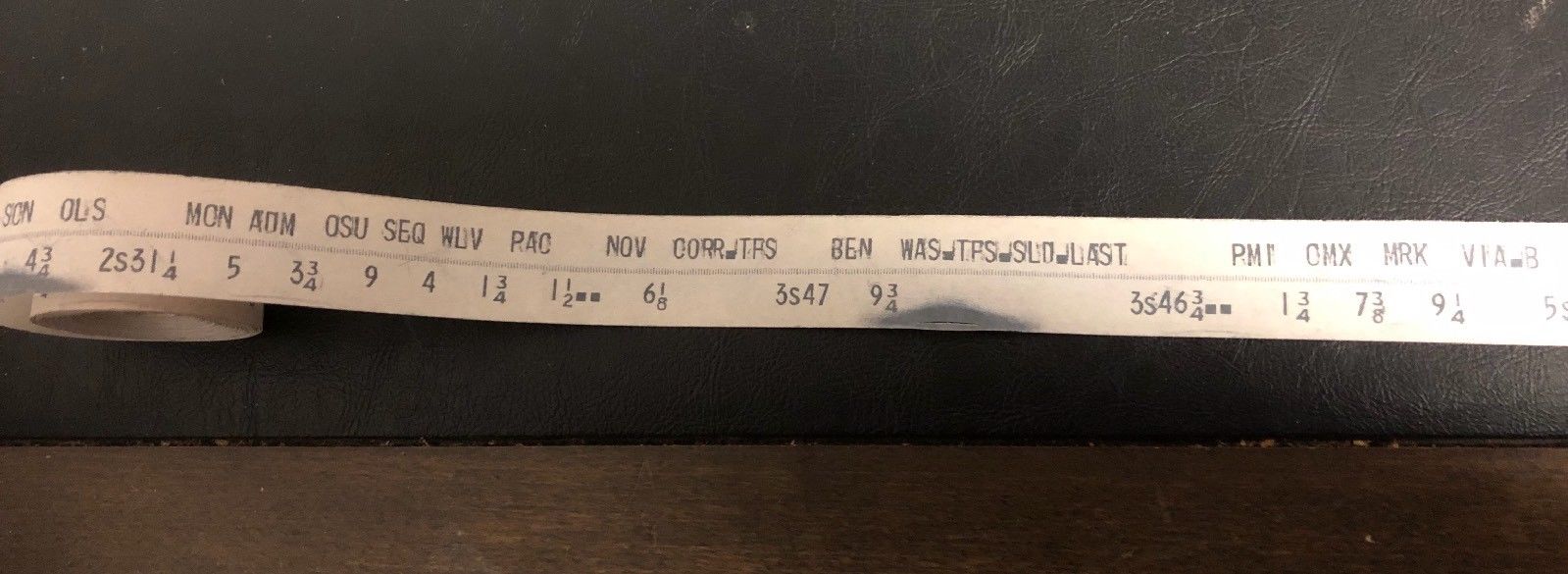

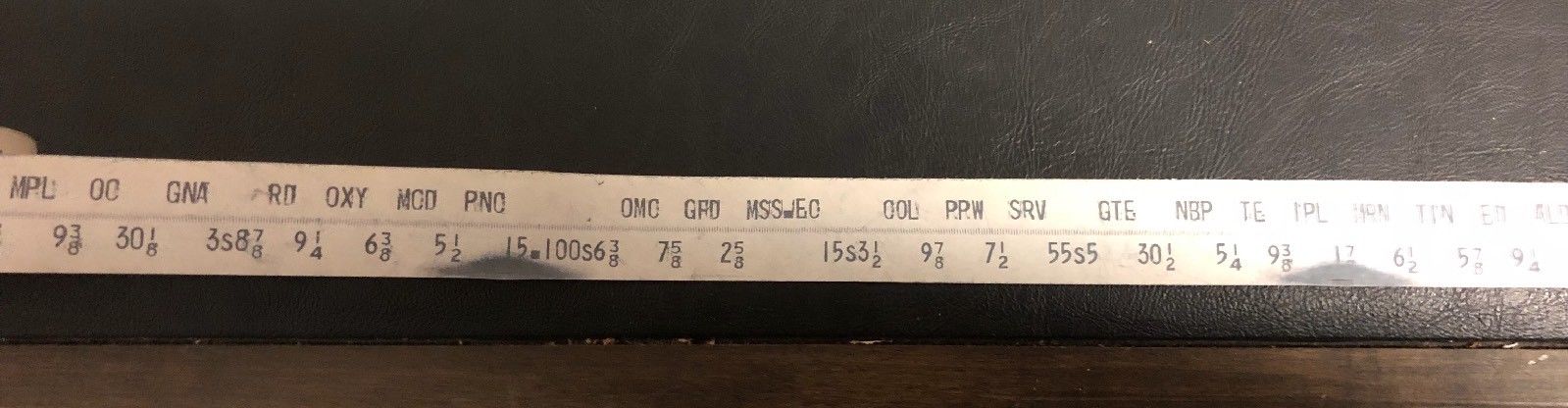

This undated TESTING MIDWEST STOCKS tape is most likely a pre-market test sent from the Mid-West exchange, in Chicago, to the NYSE in mid-1955 (the woman who sent me this is the same woman whose grandparents visited the NYSE in June 1955.) So, now I suspect that most of Herst's ticker tape was cut from pre-market tests sent by other exchanges. (Note that the stock ticker symbols and prices and their order are identical to those in some of the Herst images from 1934.) It is still possible, however, that the Peake/Chesapeake tape might be a complete fabrication by Herst himself.

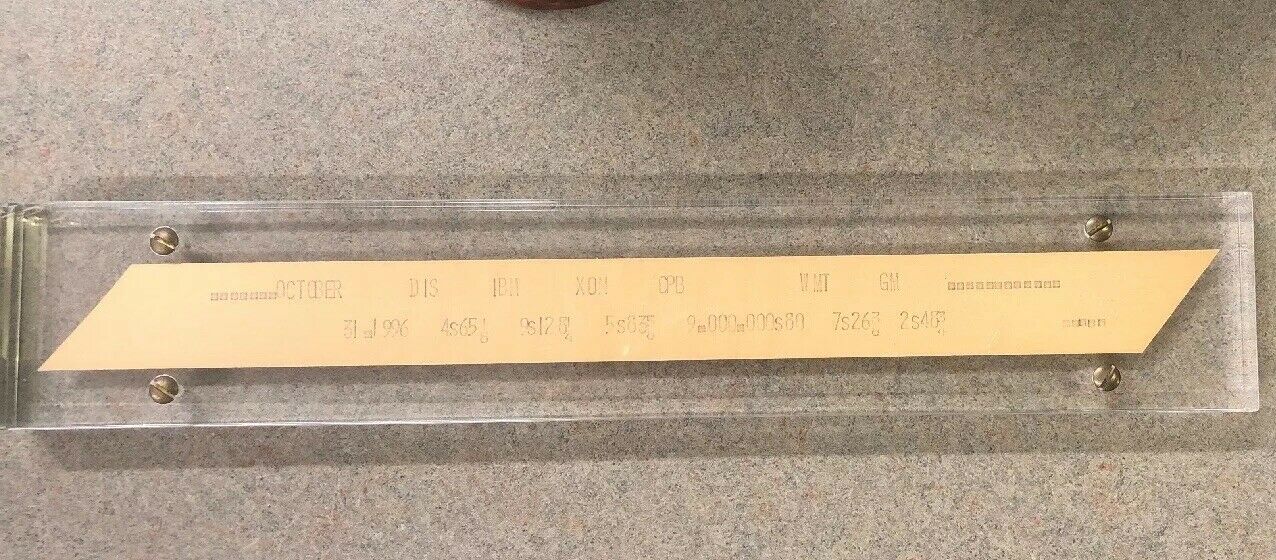

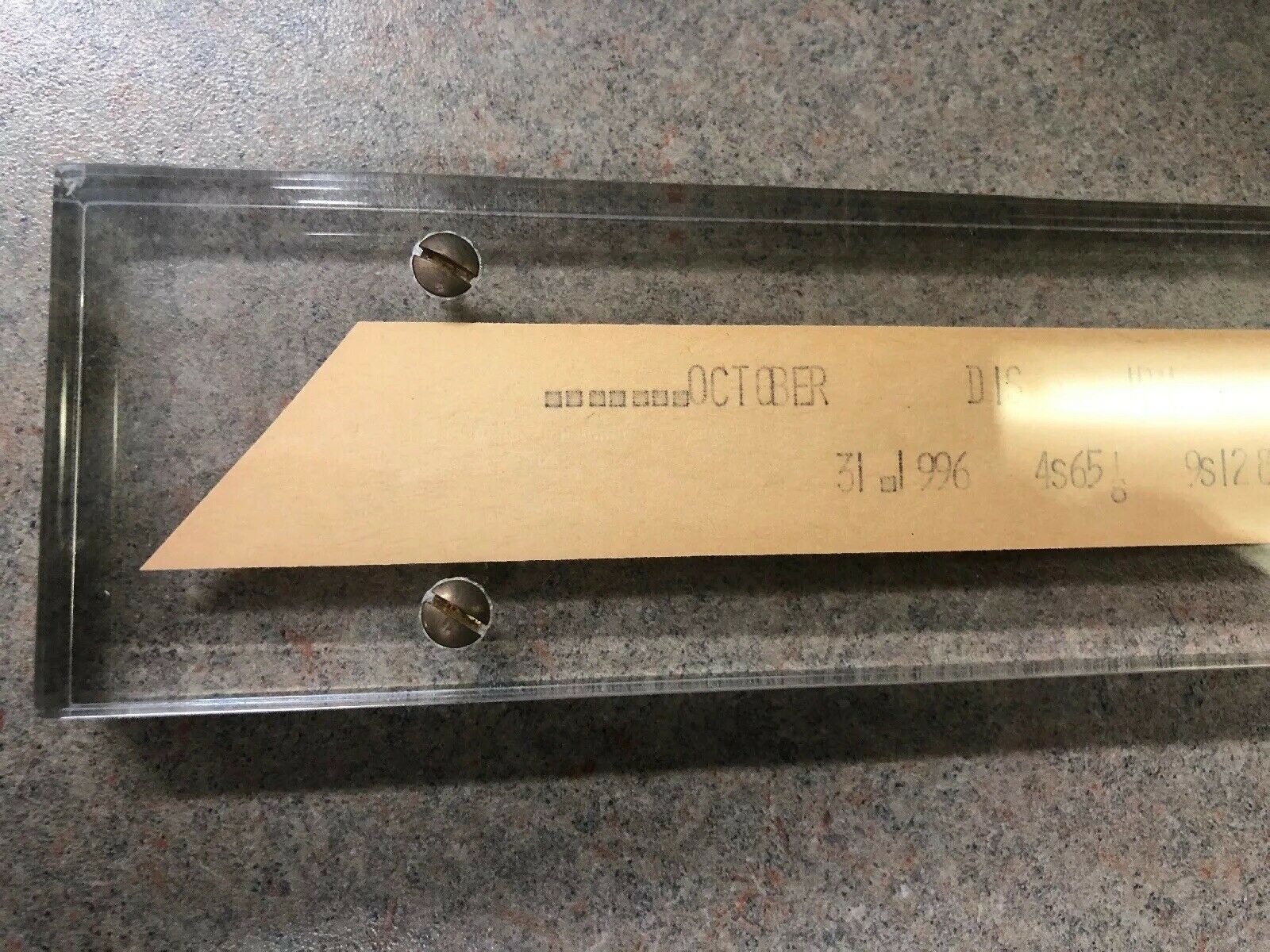

Aside: Note that the tape fragment above has diagonal cuts in it, and, in fact, cut ticker tape that you see

has often been cut on a 45-degree angle. These cuts were most likely made using a mahogany (or walnut)/chrome/Bakelite tape cutter.

The tape cutter is about 6 to 8 inches square, and looks like a small guillotine, as in the following image. You lift the little

Bakelite handle and the blade is exposed for slicing. These ones were for sale on eBay in August 2023 and November 2024, respectively, for about

$100; I have seen others for sale quite regularly.

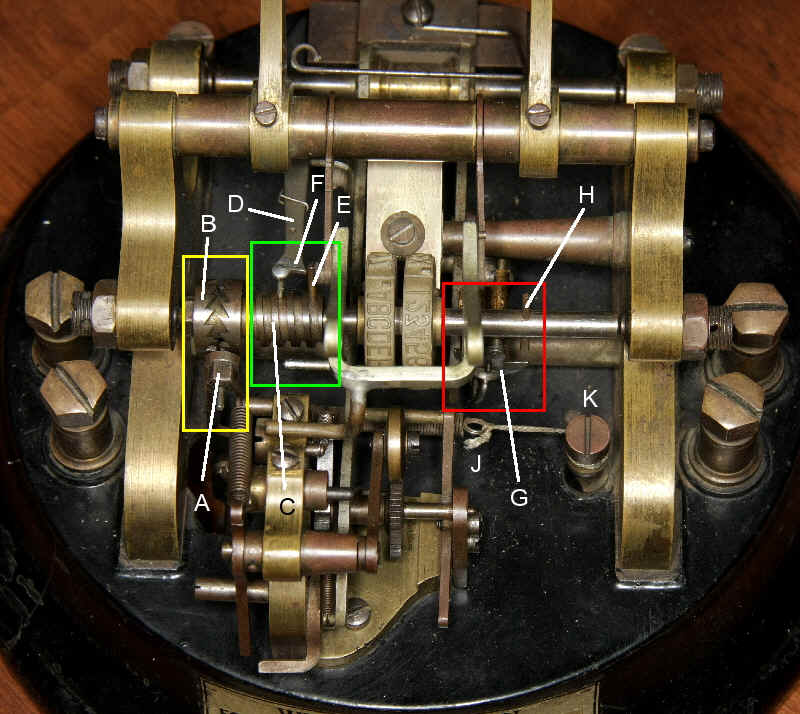

Obviously, the tape cutter is supposed to be used to cut the paper tape diagonally down from left to right. That's because ticker tape is printed with the ticker symbol in line one and then the price is offset in line two. So, if you cut diagonally down from left to right, you preserve that ticker-price pair by cutting between the symbol and the price. In the tape fragment above, however, someone (a child?) must have just been playing with the tape cutter, because none of the cuts makes any sense. In the October 1996 Fabrication above, the tape is also cut the wrong way. In the March 2005 Fabrication above, however, the tape has been cut correctly. If you look at the tape fragments on the envelopes below, you can see that in almost every case, the connection between symbol and price has been lost via a vertical cut at one or both ends of the tape, when a correctly-placed 45-degree cut would have preserved the symbol-price pair. I have seen it suggested that this cutter is for the Dow Jones broad tape, but that makes no sense to me because the broad tape is printed horizontally. The curve in the base (distorted in the second image) may be so that it can sit snuggly up against the curved base of the older ticker machines.

These price are not closing prices from October 28, 1929. So, either he just chose random prices between the historical high and low of that day, but after the fact in 1934, or he printed them during the day on October 28, 1929 and kept them for five years.

I have concluded that these ticker tapes were most likely printed in 1934, because although Herst was originally from New York, he was still a university student in Oregon in 1929. He completed a bachelor's (international law) at Reed College and a master's (journalism) at Univ. of Oregon. He did not return to New York until 1932. He worked, in quick succession, first at the NYT then the Star Ledger in NJ, before jumping to the Bond Department at Lebenthal & Co. in 1932. (Thank you to Daniel Schibley for this 1932 observation.) It seems unlikely that Herst had operator access to not only a stock ticker but some sort of test circuit for printing whatever he wanted until he was at Lebenthal, three years after the 1929 crash. He may have printed them out during a slow Saturday session, on Saturday October 27, 1934, or during his lunch break on Monday October 29, 1934 (activity tends to slow on Wall Street at lunch time), before mailing them on the Monday afternoon. Also, the self-addressed envelopes were likely recent arrivals on his desk, and the Peake-Chesapeake connection could not have been anticipated five years in advance. Thus suggesting a similarly recent fabrication.

I am sure that many people kept copies of the WSJ listing prices from October 28, 1929, which show the Open, High, Low and Last prices (indeed, I am looking at online copies of that day's WSJ, NYT and Barron's as I write this). Such a copy was likely consulted by Herst in October 1934 to construct these tapes. He likely figured that to fool people, he'd need the genuine ticker symbols to match up with genuine prices, but he could use any price he wished for the phantom symbols.

Herst was the sort of person who would jump on an opportunity. For example, I read a story of him mailing letters to fabricated addresses in Tokyo Japan as soon as he heard about the Pearl Harbor bombing, and again to Berlin Germany when war was declared on Germany, just so that he could get interestingly franked envelopes when they were subsequently returned to him as undeliverable. So, he is definitely someone who would jump on the five-year anniversary of the "crash of 1929" to market these items. Note also that someone (Herst?) has written in pencil on the Hicks envelope (BO ND) tape that it is from October 29, 1934. So, he may have printed them in the morning, using historical prices, and mailed them in the afternoon.

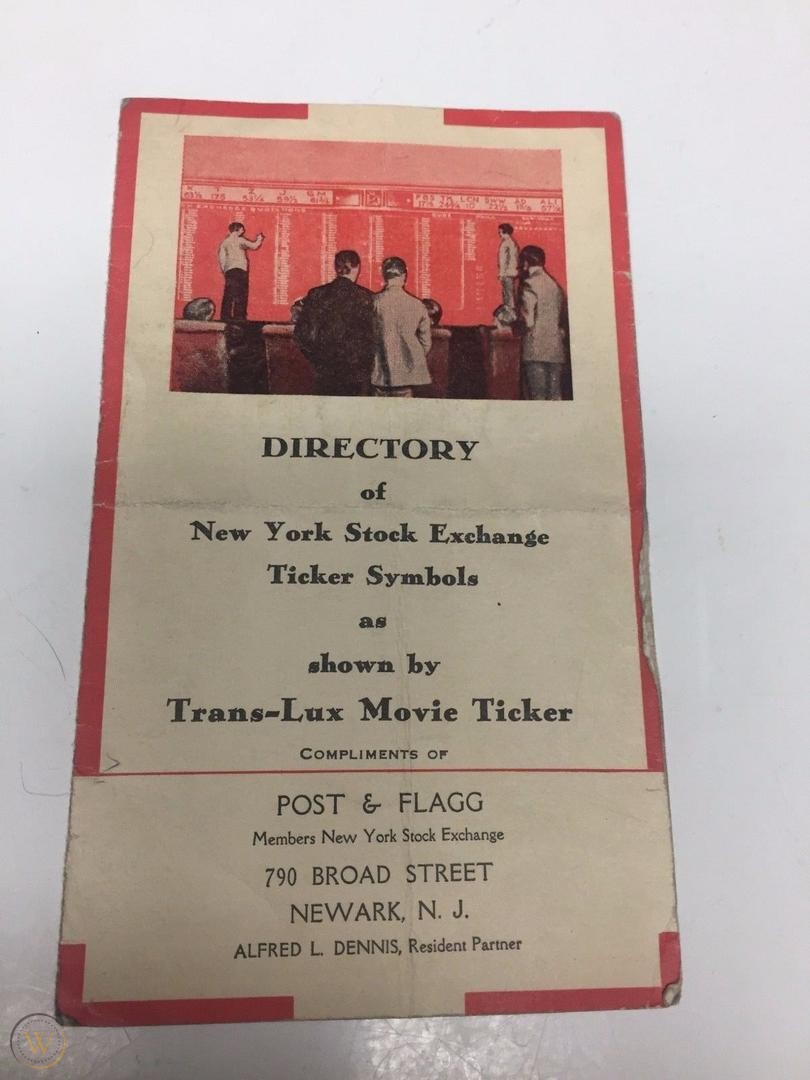

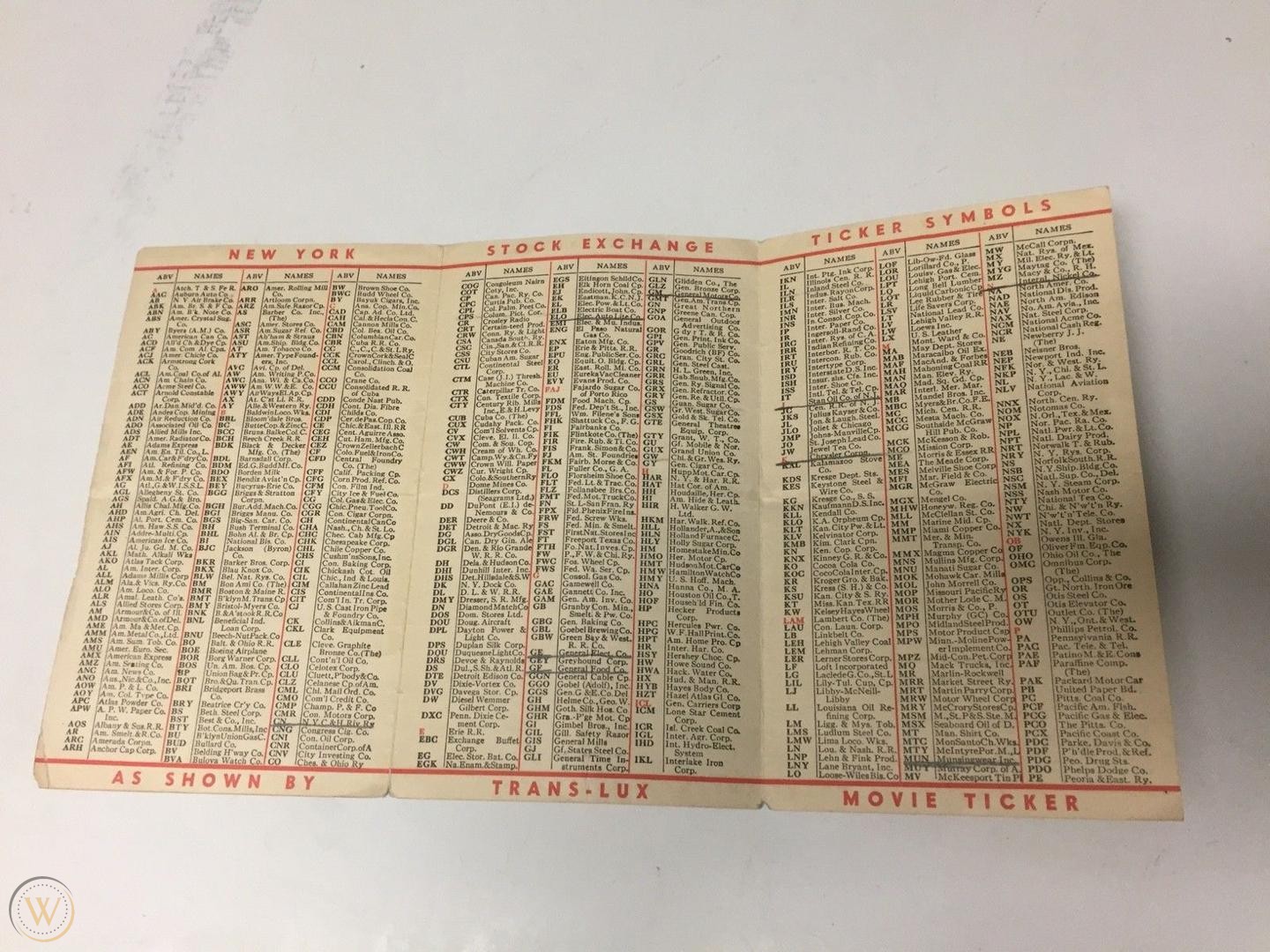

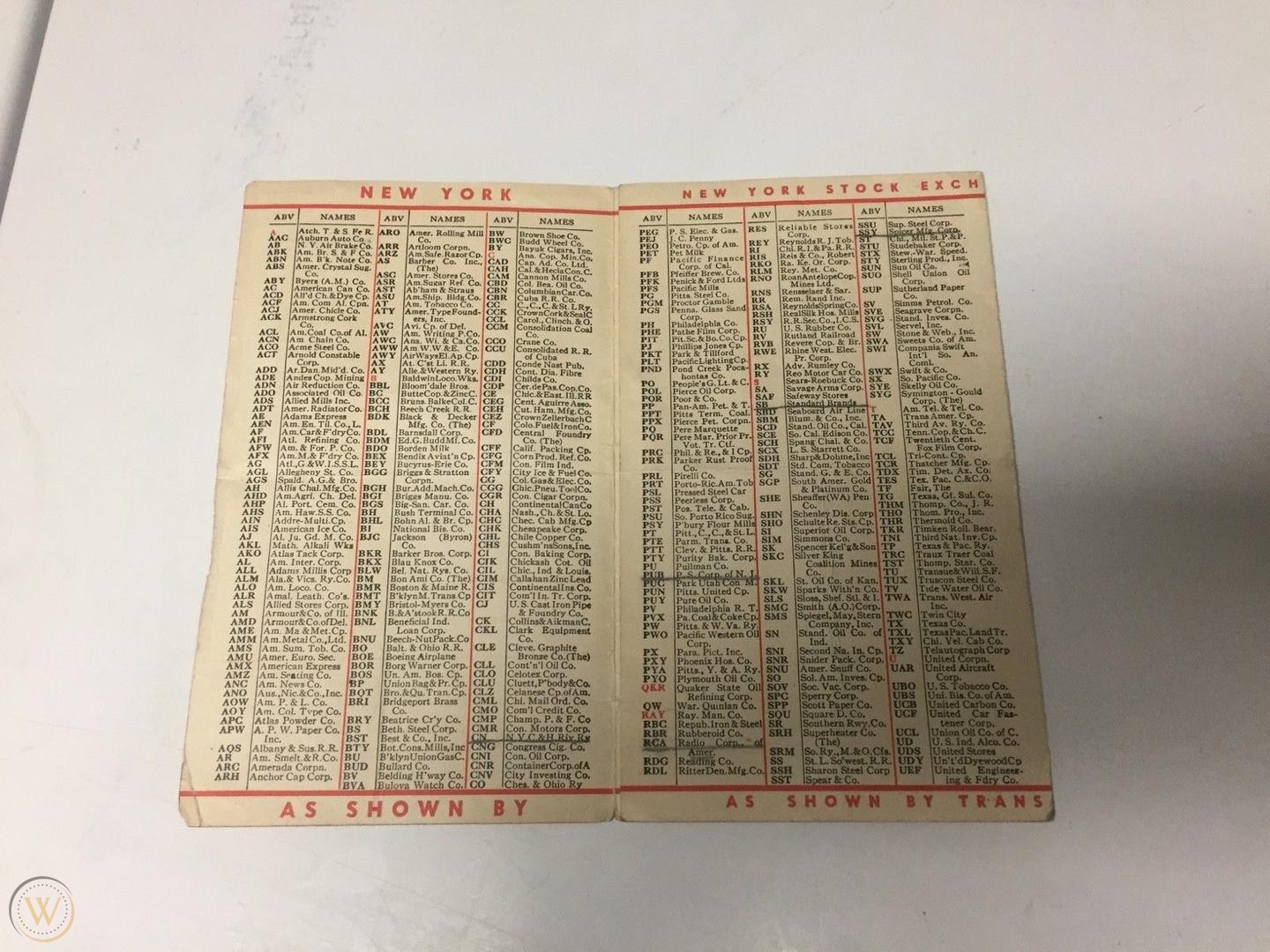

Note that the additional fabricated ticker symbols would not draw much attention for four reasons: First, the purchasers were likely stamp collectors, and not stock market experts who would notice the fabrication. Second, like today, there were hundreds of NYSE stocks that the lay person has never heard of. So, these extra symbols would be assumed by the buyer to be among those names (just look at the names in the WSJ today, or those in the Trans-Lux Directory, above). Third, unlike today, ticker symbols were not commonly used by lay persons in the 1920s and 1930s. Ticker symbols were not even reported in the WSJ, NYT, or Barron's at the time. Instead, these newspapers printed only abbreviated company names alongside prices. Finally, ticker symbols were not necessarily unique in the 1920s and 1930s. That is, different exchanges used slightly different symbols for the same stock. The bottom line is that fabricated symbols would not draw attention to themselves in Herst's context.

For completeness, note that I see that the NY City postage was only two pennies, whereas the other letters required three pennies. Note also that Herst's tape is the narrow 3/4"-wide tape as compared with the 1"-wide tape seen in most of the envelopes below from the late 1960s.

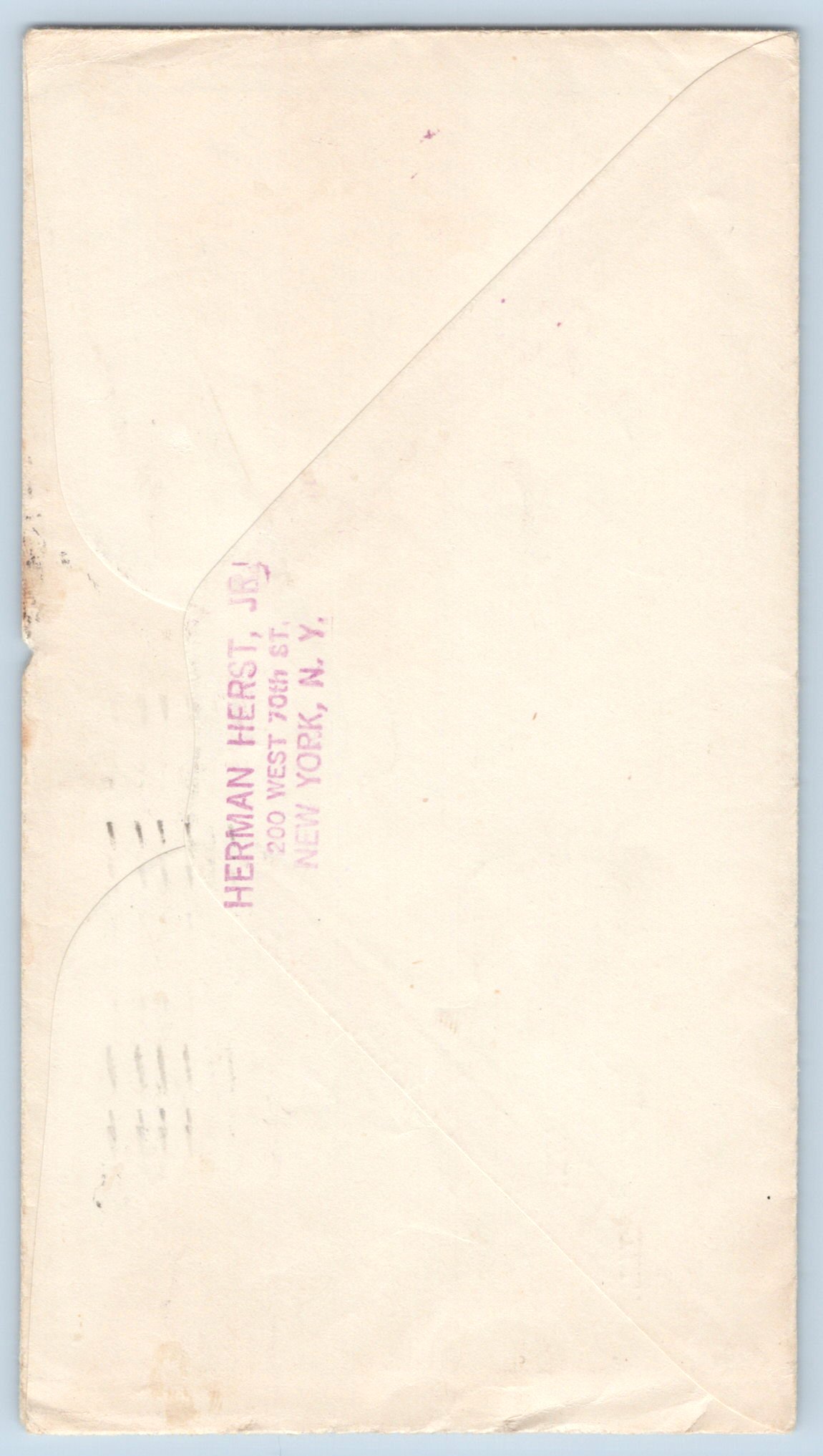

Finally, before looking at Herst's envelopes, note that the return address on Herst's envelopes is 200 West 70th Street, on the Upper West Side.

That apartment building was built in 1926 and is shown below. It is coming up to 100 years old, but must

have been near new when Herst moved in. It is about five and a half miles north of the NYSE (and Herst's office) as the crow flies.

| Two Final Mysteries |

A reader was told in 2021 that this item is stock exchange ticker tape from the 1920s, and he asked me about it. No, it is not a stock exchange item. After 18 months of asking people about it, a New Zealand–based Tibetan head monk who was then in India told me that it is Tibetan script of the mantra of compassion—om mani padme hum. It would have been rolled up tightly inside a prayer wheel. I think it was block printed by hand. After some searching, I found a very similar looking item for sale, including both prayer wheel and script, dated to 1800. I suspect that this is of a similar vintage. I left the images here in case anyone else has something similar and is similarly confused.

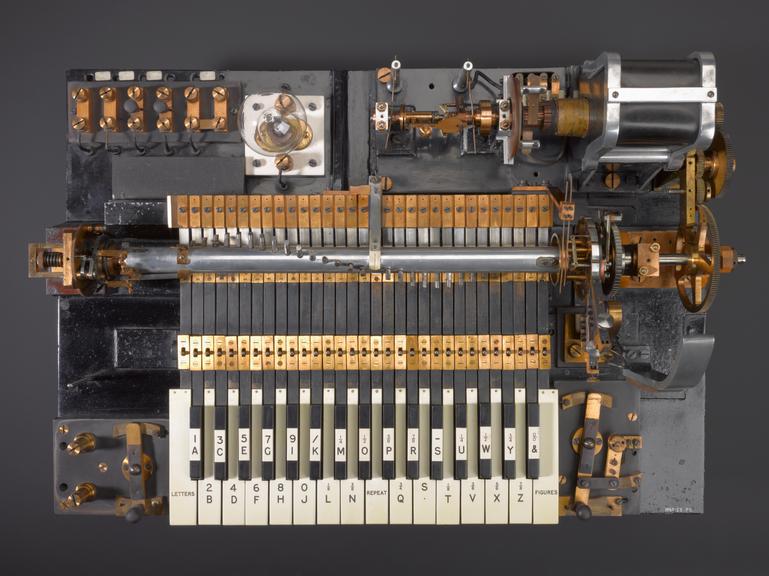

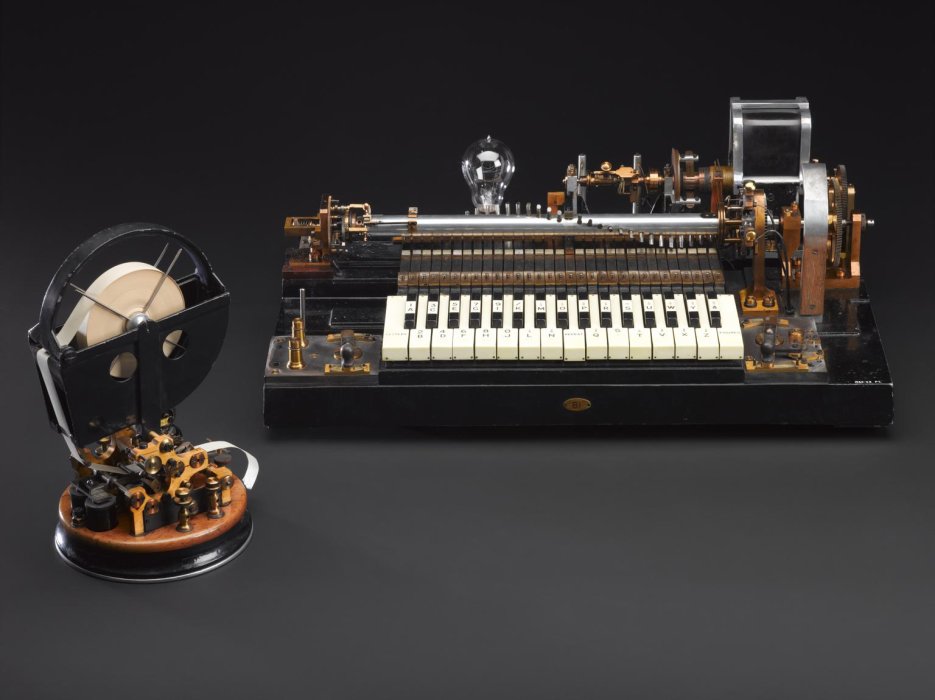

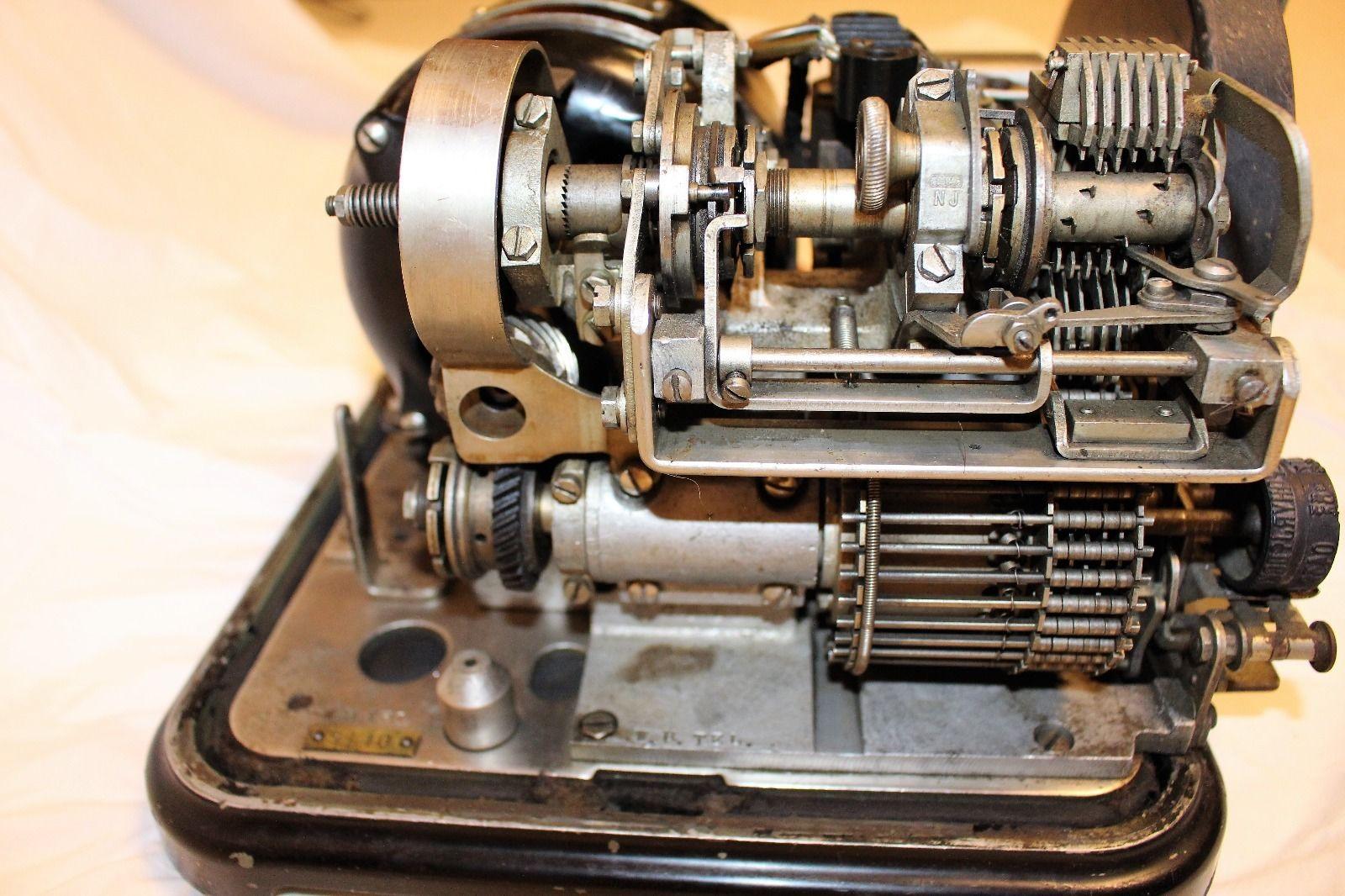

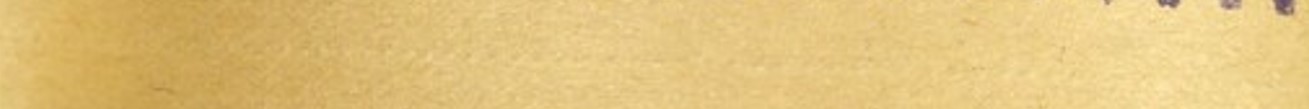

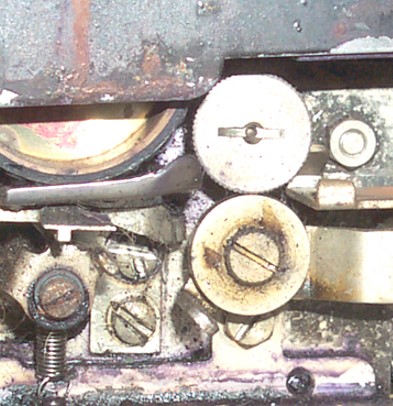

In December 2024, I saw the following item for sale on eBay, listed as a Stock Exchange Ticker Machine.

It was obviously not a stock ticker. After some investigation, I decided that it was a Frankenstein creation. An Elliott Brothers (London) 1880s telegraph tape real (perhaps from a manually-wound Morse telegraph station) had been coupled with a 1960s Thorens pillar and plate turntable motor to make it a self-winding (or perhaps non-winding) device. If you think it is something different, or have any comments, please let me know.

| References |